The portents of market failure—things like inadequate information and a lack of competition—are everywhere in public education. So, when it comes to school choice, government has an important role to play: reducing information asymmetries, bolstering accountability, and ensuring fairness. But the market for schooling also needs bottom-up, community action if it’s going to work for families in the real world. That point was evident at the recent Portfolio Network meeting hosted by CRPE in Camden, New Jersey.

The Portfolio Network meeting is an annual gathering of innovative district, charter school, community, and civic leaders from across the country who are figuring out how to run and oversee autonomous schools of choice in ways that ensure all families have good options and the system operates fairly.

At the meeting, I facilitated a session with my colleague Sarah Yatsko about the ways in which school choice can break down for families in the real world and what leaders in cities can do about it. The results suggested that “managing” competition takes both government and community.

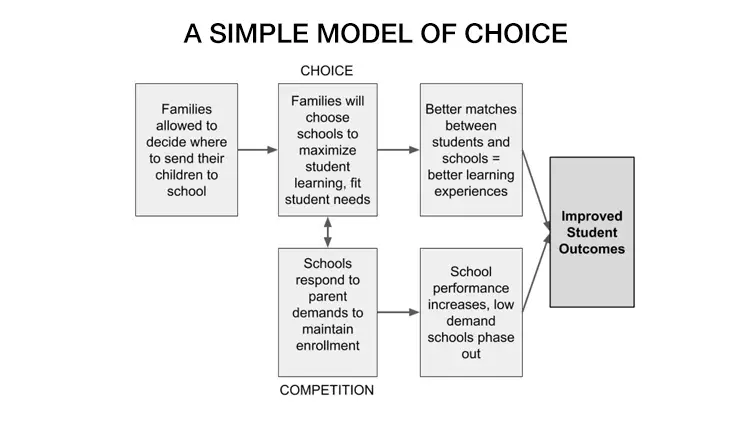

We opened our session with a simple model of how school choice, at the most abstract level, is supposed to work.

The narration of the figure goes something like this:

When families are able to choose their public school, they can choose a school that fits their child’s educational needs. When schools must compete for students, they will respond by improving and evolving to meet the demands of “customers” or risk going out of business. In theory, the end result will be better schools that better serve children’s needs.

After presenting this simple model, we asked session attendees (including district and charter school leaders, community leaders, and nonprofit managers) to jot down on a sticky note their answers to this question: Where and how might the theory of school choice break down for families in the real world? The sticky notes covered the wall. Here’s a sampling of what they said:

- Families might not know a good school when they see it

- Families might not have transportation to the school they want

- Families might need to prioritize safety over academic quality

- Schools might mislead parents about their program

- Schools could cream the best applicants

- Bad schools often stay open

- Good schools are in short supply

After surfacing all of these problems, the group then talked about what cities and school systems can do to address them. Here’s where we heard about the role of government and community.

On the importance of government, for example, Brian Eschbacher, executive director of Planning and Enrollment Services in Denver Public Schools, described policies and systems in Denver that help make choice work better in the real world: a streamlined enrollment system to make choosing easier for families, more flexible transportation options for families, a common performance framework and accountability system for traditional and charter schools to ensure all areas of a city have quality schools, and a system that gives parents the information they need to choose schools confidently. In fact, my CRPE colleagues and I spend a lot of time studying and talking about what it takes to design and implement policies like these, especially in cities where the schools are made up of a mix of district and charter schools and multiple oversight agencies existing side by side.

Then we heard from Sarah Carpenter and John Little, community and family advocates from Memphis Lift. Sarah suggested that district policies are important, but they aren’t enough. Families, especially those in low-income households, need additional social supports to be confident choosers. They need help building a mindset that understands they actually have a choice and can exercise it. They need a network of other adults they trust who know about school quality and, specifically, about the quality of the available schools, to help them understand their options. And they need to be part of a broader constituency that demands—not just by voting with their feet but by collectively voicing their concerns—access to quality schools.

Making school choice work requires bureaucratic policy solutions, often technical ones, to make the market for schooling more fair and responsive. But making school choice work also requires engaged and mobilized families who can help address the human side of choice and competition in schools. Cities with lots of school choice face technical and human problems; they need to encourage and embrace both types of solutions.