With the election of President Donald Trump and the appointment of Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, it may seem like school choice is having its day, poised to gain momentum. But ask any educator or community leader in a city with lots of school choice already, and they’ll tell you choice alone isn’t enough. Instead of promoting choice and letting the chips fall where they may, thoughtful leaders in cities across the country know that governments and their partners and choice advocates have important, challenging work to do if they want school choice to truly benefit families in the real world.

Take the example of Cleveland, OH. Five years ago, civic and education leaders in Cleveland launched the Cleveland Plan for Transforming Schools with the goal of ensuring that “every child in Cleveland attends a high-quality school and that every neighborhood has a multitude of schools from which families can choose.” These were ambitious goals for Cleveland’s schools, given their academic and financial challenges. As the Plan’s authors explained:

In the 2010-11 school year, 55 percent of Cleveland schools (district and charter) were in academic watch or academic emergency … [the Cleveland Metropolitan School District] faces a $64.9 million budget deficit in 2012-13 … [and] more than 30,000 students have left the CMSD over ten years.

Cleveland was also a “high-choice” city, where families could choose from a wide mix of district schools and charter schools.

All of the factors facing Cleveland—low academic performance, financial strain, enrollment loss, charter school competition—are familiar to many urban school systems. But Cleveland also had a problem that might sound surprising: some of the city’s highest-performing district schools and charter schools were underenrolled. Families were choosing low-performing schools over higher-performing schools—even when the high performers had room to spare. Maybe this was because they wanted to stay in the neighborhood, or were concerned about how their child could safely get to another school, or didn’t know there were open slots at good schools. Whatever the reason, Cleveland’s civic and education leaders knew that the problem didn’t have a simple solution. So, among the Plan’s many strategies to improve schools systemwide, Cleveland’s leaders did three key things in an effort to increase the demand for quality:

Streamlined Enrollment. Instead of asking families to fill out separate applications for each school, the Plan called for a citywide enrollment system that would streamline the process and hopefully make it easier for families to choose higher-performing schools over lower-performing ones. Today, families in Cleveland can use an online enrollment portal to choose from among district schools across the city and discussions are underway to include charter schools in the system.

Provided Families with Information. Cleveland recognized that a streamlined enrollment process alone wouldn’t be enough to shift demand toward quality; families also need better information. In addition to its website, the Cleveland Metropolitan School District used its social media to give students and caregivers a virtual visit to different schools. The Cleveland Transformation Alliance, a nonprofit created to support the implementation and success of the Plan, distributed 30,000 copies of its School Quality Guide that includes profiles of schools, school ratings, student demographics, and school contact information. The Alliance also mailed 17,000 postcards to promote school information available on its website and supported a media campaign that reached an estimated 1.2 million people through printed books, billboards, kiosks, web ads, and print ads in local media.

Provided Families with Support. Even with a streamlined enrollment process and better information, Cleveland recognized that families also need social support to choose better schools for their children. So the Cleveland Transformation Alliance and its partners supported 30 “School Quality Ambassadors” to lead community events about schools and school quality and to provide one-on-one support to individual families. Families could also learn about schools at a new “school quality fair” organized by the Alliance and its partners, which showcased fifty K–8 and preschool programs selected because of their high performance and school district-sponsored school fairs. The district also hired recruiters to help new families and returning Cleveland residents learn about their school options. And Cleveland’s True2U mentorship program for 8th graders included help with choosing a high school.

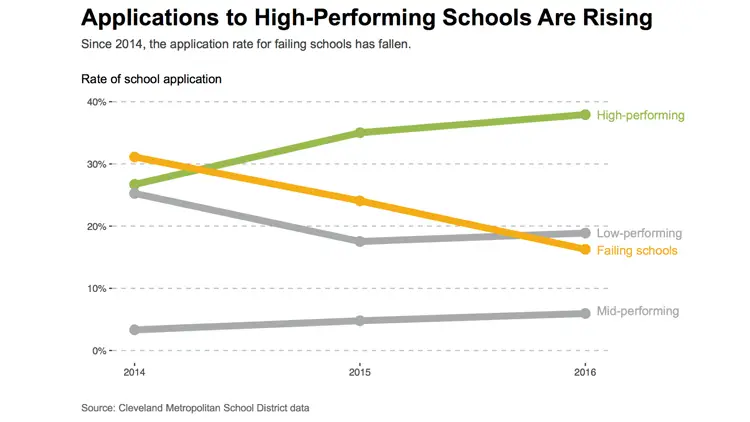

Early evidence suggests these efforts may be paying off. Among the families that submitted applications to the citywide enrollment system over the last three years, it appears that, over time, more families are selecting the city’s highest-rated schools and fewer are selecting its failing schools. In 2014, 27 percent of applicants selected and were assigned to the city’s high-performing schools. When we looked at how many students applied and were assigned to those same high-performing schools in 2016, the number rose to 38 percent. At the other end of the spectrum, the share of applications to failing schools dropped from 31 percent to 16 percent.

It’s worth noting that our data only provide us with the school to which students were assigned through the application process and not all the choices families listed on their application. However, we know that in 2016, 89 percent of students were assigned to their first-choice school and another 7 percent were assigned to their second-choice school. So, the “assigned” school was the first choice for the vast majority of applicants and at least the first or second choice for all but a fraction of students. Since high-performing schools had perpetual vacancies leading into this period, the increased assignment to high-performing schools reflects different choices being made by students.

Of course, we can’t really know the extent to which these shifts were driven by Cleveland’s demand-side policy initiatives or by shifts in the supply side of the equation, including the district’s investments in starting several new and innovative schools. The chart above also makes it clear that some families in Cleveland still choose low-performing schools, probably for reasons the Plan hasn’t yet or can’t address: a lack of transportation to better options or the pull of neighborhood history that can make a low-performing school seem like a good choice.

But the trends look promising. So too does the fact that Cleveland’s leaders, like those in other high-choice cities, understood that when school choice breaks down in the real world, government and its partners have a role to play with smart engagement and policy to make it work better for families and cities.