The work of post-pandemic learning recovery will take many years. As researchers Tom Kane and Sean Reardon noted in an opinion piece in The New York Times: “Especially in the hardest-hit communities, it is increasingly obvious that many students will not have caught up before the federal money runs out in 2024.”

Schools are hungry for cost-effective strategies that can help students accelerate mastering foundational academic skills. One tutoring approach that has significantly raised math achievement in a dozen countries is worth a look for U.S. schools. The idea relies on basic technology and has a personal twist: Schools close targeted skill gaps by involving the family when tutoring students over the phone.

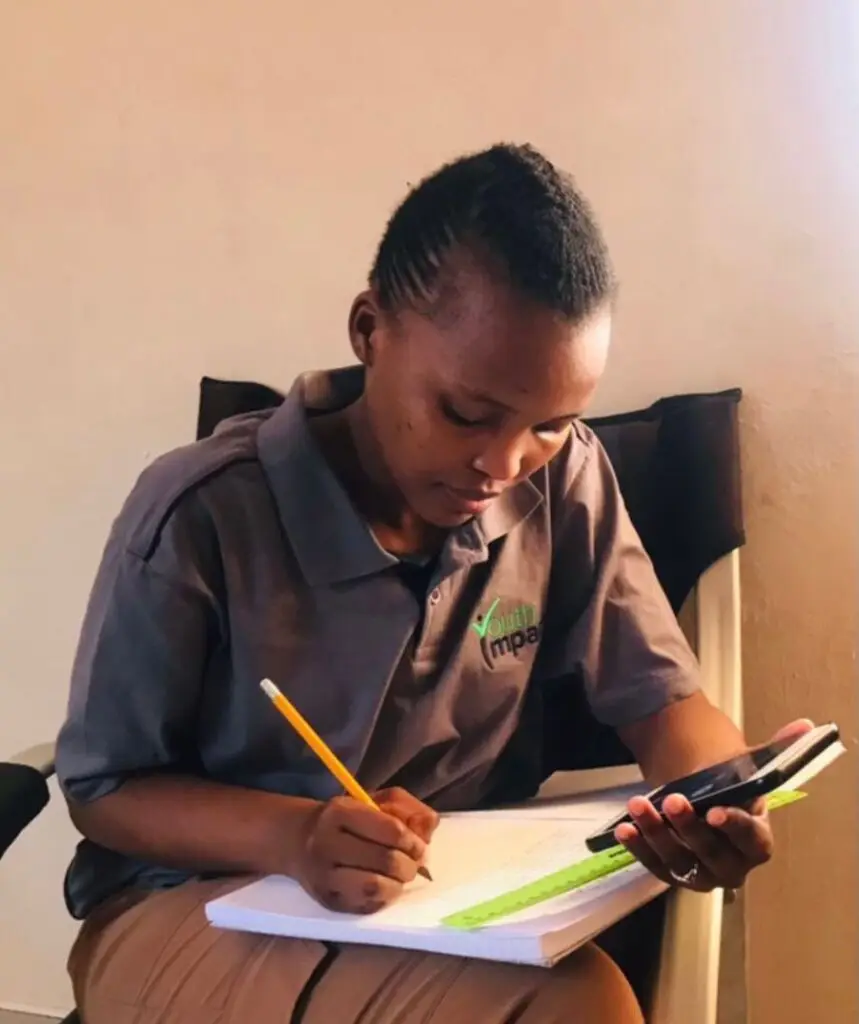

Tutoring students via cell phone

The ConnectED program was first carried out in Botswana by Youth Impact, a nongovernmental organization, during the 2020 school closures. After a phone call explaining the program to parents or caregivers, a tutor conducted an initial diagnostic assessment of the student’s skills. The tutor then texted two math problems weekly, and followed each text with a pre-scheduled 20-minute phone call with the student and parent together to learn and solve the problems.

The program produced dramatic gains in student learning. Further research identified the key to the intervention’s success: the tutor and caregiver jointly motivating and supporting the student.

After ConnectED’s initial success, organizations in 10 countries adopted the strategy, including Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Argentina, Uganda, Kenya, India, Nepal, Indonesia, and the Philippines. A team of researchers led by Naom Angrist of Oxford University studied the family phone tutoring approach in five different countries and found that it ranks in the top percentile of cost-effective education interventions for accelerating academic learning. It also increased student motivation and engagement.

Mpho was adamant. “Schedule more time with my tutor!” His mother, Masego, sighed. “I told you, we don’t have any more sessions. You caught up, so our sessions are finished.” “But I want more! Text him! Please?” Tears. Smiling wistfully, Masego tries to find another way, “I’ll ask for more math questions that you and I can do together, at least.” Reassured, Mpho goes off to play. His mother is proud that Mpho has caught up to his grade level thanks to the family phone tutorials and happy to see his enthusiasm for learning.

A real-life success story of SMS tutoring, shared by our colleagues at ConnectEd.

Personalization and family involvement are key

As the phone tutoring approach spread, organizations in other countries varied the program design. For example, some tried the intervention with middle school students instead of elementary students. Some focused on literacy skills or social-emotional strategies in addition to math. Some used classroom teachers or volunteers instead of paid tutors. Some carried out the tutoring for different amounts of time.

These variations helped researchers identify three elements essential to the intervention’s effectiveness. They are:

- Personalized content: The tutoring must fit the student’s assessed needs. The tutor must conduct an initial diagnostic assessment to identify which foundational skills the student has not yet mastered, then focus the questions sent via text and the phone lessons on those gaps. Each tutoring call ends with a mini-assessment to verify mastery and identify the next topic. In international education circles, this approach is called Teaching at the Right Level, and the World Bank classifies it as a cost-effective education strategy. Naeha Dean, chief strategy officer at Accelerate, a national nonprofit that promotes tutoring, said: “There’s widespread recognition that personalization is key. The best tutoring programs meet students where they are, conduct early diagnostics to target the tutoring, and adapt to students’ needs.”

- Family engagement: Involving the student’s parent or another caregiver in tutoring led to greater learning. In fact, when parents led the second half of tutoring sessions, the average improvement in learning jumped three-fold, researchers found. Even when the caregivers themselves hadn’t mastered the material, their engagement contributed to their students’ learning. This aligns with growing evidence that suggests when parents know their child’s learning level, they can better support the child’s education. It can also help parents themselves – many of whom have anxiety about academic subjects like math – to develop a growth mindset that transfers to their children.

- Human connections: The human connection begins during the first call with the caregiver explaining the program, securing participation, and setting expectations. The relationships between caregiver, student and tutor deepen throughout the phone tutoring session and become motivating for the student. Even the process of scheduling the tutoring calls can help strengthen the tutor-caregiver relationships. In this way, the approach bucks the trend of looking to AI and other technology solutions. As Susanna Loeb of the National Student Support Accelerator points out: “Sustained and strong relationships between students and their tutors are an important element of high impact tutoring of all types.”

Could family phone tutoring work in U.S. schools?

The nonprofit Springboard Collaborative has developed Family Educator Learning Accelerators, a program which helps schools leverage out-of-school time by having teachers train parents as literacy tutors for their own children. Participating students accelerate their reading proficiency by an average of four months in a five to 10 week program cycle, with bigger gains for students who started the farthest behind. Massachusetts’ state education department recently evaluated literacy interventions and found the Springboard tutoring to be a cost-effective model and recommended expansion. Alejandro Gibes de Gac, founder and CEO of Springboard Collaborative, wasn’t surprised. “Looping families in and equipping them with tools to support student learning is like magic,” he said. “Families are one of the best levers that schools have to accelerate learning.”

The basic technology required for this kind of tutoring would not be a barrier for most U.S. families, as 97% of Americans have a cell phone (and 82% have a smartphone). Widespread availability of family-school communication tools could also help facilitate this strategy. For example, the not-for-profit organization Talking Points offers a widely-used, free-to-teachers platform for family-teacher text-based communication with real-time translation that could reduce the time required to schedule the phone tutoring sessions and easily create an interaction data record for future analysis. Similarly, ParentPower’s Ready4K program has seen success sending texts of early literacy learning activities to help caregivers engage with students on academic content.

Like most current tutoring programs, the major cost for this intervention is the tutor’s time (unless the tutors are volunteers). The team at ConnectEd advises schools and organizations to make sure tutors have enough time to do the work. Tutors don’t need to be physically present in schools for sessions, but they still need to receive training, conduct the initial assessment, prepare personalized lesson content, schedule the tutoring calls, and conduct the tutoring sessions.

Family phone tutoring is not a substitute for strong classroom instruction. But compared to in-school intervention models, this approach broadens the pool of available tutors to include house-bound retirees, alumni in college, volunteers with day jobs, and folks with mobility challenges. Since no physical space or expensive equipment is needed, programs can get started with minimal upfront expenditure. It can be done by any type of youth-serving organization, not only schools.

Loeb from the National Student Support Accelerator urges school systems to consider which contexts this strategy may be well-suited for, find tutoring partners who can help with implementation, and most importantly, prioritize students who are most in need of support.

Interested in learning more about this practice and how to adopt it?

Explore ConnectEd’s implementation guide