The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted public education in ways that were unimaginable at the beginning of the year. Students, parents, and teachers have struggled to make remote learning work. Many classrooms remain closed and schools have lost touch with scores of students.

We also saw remarkable examples of innovation, ingenuity, strength, and commitment to supporting student success. Working with a diverse group of researchers, we are partnering with The Barr Foundation to uncover these examples and learn from them.

Our focus is on New England—a region that reflects America with diverse metropolises, vast rural areas, and increasing diversity in communities and schools. With the first compulsory education law dating back to 1642, the region has long been a test-bed for new ideas to improve education.

Our research aims to show how school systems are adapting and innovating in the face of the pandemic, with a particular focus on efforts to sustain learning for high school aged students—those with the shortest runway to recover any lost learning time. Adolescents face unique challenges and opportunities during this crisis as they navigate peer and family relationships, flexibilities around when, where, and how learning occurs, and pivotal post-secondary transitions.

Today, we release the first analysis stemming from the project—a comprehensive review of 80 school districts’ reopening plans and reopening guidance from the six states that make up the region (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont).

Our first look suggests that the New England region’s success in driving down community transmission rates may have opened more possibilities for in-person instruction. But the region’s work to reel in the public health crisis did not translate into definitive actions on all the issues confronting students this fall.

While overall remote learning plans are more comprehensive than what we saw in the spring, less than half of the districts we reviewed communicated plans in place to identify learning loss, and even fewer identified evidence-based strategies, such as tutoring, to address gaps in learning. State leadership provided a bulwark against inaction in some cases by requiring districts to put in place plans to address the learning challenges facing students. Whether these measures are enough, how school districts’ responses evolve over the course of an unpredictable pandemic, and what promising new approaches emerge will be important to watch in the months to come.

Lower community transmission may have made more in-person learning possible in New England

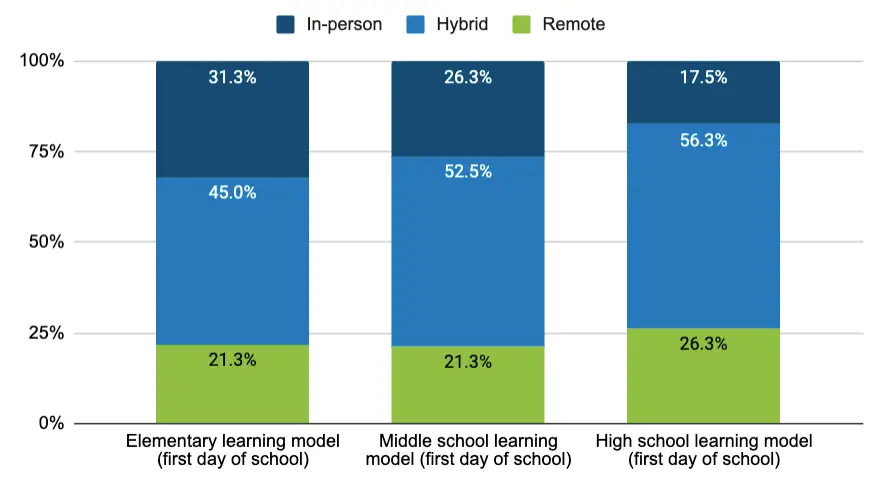

Since last spring, New England has stood out as a model for minimizing communitywide transmission of COVID-19. The region’s public health success appears to have borne some fruit in terms of the number of districts offering students at least some in-person instruction. Just 26 percent of school districts in our review started the school year with no in-person instruction for high school students. Elementary schools were more likely than middle or high schools to open in person.

Our sample, though not statistically representative, is designed to include the largest districts by enrollment in each state and to include high-poverty, rural, urban, and suburban districts from each state. (The average sampled district has 18 percent of students living in poverty; 40 percent of the districts have more than 20 percent of students living in poverty.)

The schools we reviewed were much more likely to offer a hybrid learning model in which students attend classes both in person and remotely, compared to their peers nationally: 56 percent of districts reopened their high schools under a hybrid model. Nationally, just 12 percent of school districts (across all grade levels) planned to reopen under a hybrid model, according to our analysis of a nationally representative sample of school district reopening plans in mid-August.

Start of Year Learning Model by Grade Level

Source: Based on CRPE’s analysis of 80 New England districts’ publicly available fall learning plans as of October 19, 2020.

But variation in access to in-person learning suggests more action may be needed to support in-person learning for all students

Of the six states in our study, Massachusetts had by far the largest number of school districts opening remotely for high school students at the start of the school year (50 percent). In contrast, just 10 percent of Connecticut districts and 8 percent of New Hampshire districts we looked at opened high schools remotely. These differences reveal some of the limits of an approach to reopening schools that relies simply on driving down communitywide transmission rates.

While states recommended that districts consider a return to in-person learning, it didn’t always have its intended impacts. Massachusetts’ reopening guidance took pains to encourage districts to reopen for in-person learning; it was one of the few plans we reviewed in our 50-state analysis that included a comprehensive review of the literature on COVID-19 transmission in schools and presented summary recommendations based on a convening of the state’s world-renowned medical community. And yet, many districts still decided to reopen remotely.

Others have noted that Gov. Gina Raimondo of Rhode Island fully leveraged her bully pulpit to advance the cause of in-person learning; the result ultimately bore fruit with many more schools opening for instruction.

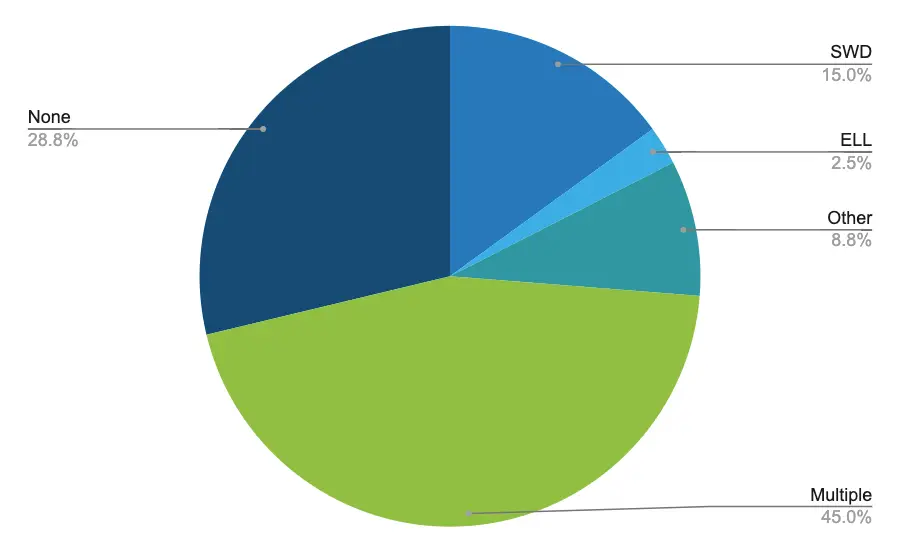

Vulnerable students prioritized for in-person learning but gaps in access remain

Almost three-quarters of school districts in our sample say they will prioritize at least one vulnerable student group for in-person learning and 45 percent say they will prioritize multiple vulnerable student groups. In official guidance, both Connecticut and Massachusetts emphasized the need to support students with disabilities with in-person learning opportunities wherever possible and even when other students were learning remotely.

New England District Plans Often Prioritized One or More Vulnerable Groups for In-Person Learning

Source: Based on CRPE’s analysis of 80 New England districts’ publicly available fall learning plans as of October 19, 2020.

Districts in our sample that serve larger numbers of students living in poverty are more likely to open remotely. Compared to districts with a community poverty rate below 20 percent (the regional average), higher-poverty districts are about two times more likely to open high schools remotely (37.5 percent vs. 18.8 percent).

Nationally, we found that income disparities were in part a function of urban districts opening schools remotely, but this pattern was not especially present in the New England sample. Of rural high schools in our sample, 26 percent opened remotely—only somewhat lower than the 38 percent of urban high schools in our sample. Rural elementary schools in the New England sample are as likely to open remotely as their urban peers in New England (26 percent vs. 25 percent).

Remote learning plans this fall appear more robust than last spring, despite variability in state guidance

Last spring, after schools around the country closed in the face of the pandemic, most districts struggled to offer students a comprehensive educational program—including structured curriculum, instruction (live or recorded), and feedback from teachers on student assignments. States made efforts to offer guidance but many failed to set clear expectations for what remote learning should look like or how to monitor district progress.

Our review of state and district plans in the New England region suggest some improvement to meet these challenges in the fall. Three states in the region—Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island—offered more comprehensive and definitive guidance on school district reopening. All three states required districts to:

- Prepare for in-person, hybrid, and remote learning scenarios

- Submit a comprehensive reopening plan to the state

- Put in place specific practices to support student learning in remote or hybrid learning models, including for students with disabilities.

These states’ approaches stand in contrast to the other states in the region. Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont tended to take a more hands-off approach to supporting district reopening. To be sure, these states offered recommendations and some supports. But many of the details were left up to local districts to decide.

Despite these different state contexts, across the board, New England districts’ fall reopening plans often provided improved or more structured remote learning experiences compared to last spring. Chelsea, in Massachusetts, even called its plan “Remote Learning 2.0.”

All eighty districts in our review committed to providing curriculum and instruction during remote learning. All but five made it clear teachers would provide feedback on assignments, and all but one provided real-time instruction. Holyoke Public Schools in Massachusetts, for example, explicitly stated the lack of synchronous learning that occurred during the spring and decided to implement required daily synchronous learning for their students.

In other words, factors other than state guidance—such as feedback from parents coupled with the advantage of time to plan—may have played a larger role in driving local school systems to offer more comprehensive educational programs in the fall than in the spring. But state guidelines likely did shape other aspects of districts’ plans—including the number of days they planned to provide instruction.

Although it was difficult to find complete information, districts do not seem to be offering extended days or planning for extended school years. The average district had 174 days. Instructional time seemed in large part to be a function of state minimums. Districts in Massachusetts averaged 171 days, reflecting state guidance that allowed them to reduce the year to 170 days. Connecticut’s districts, by contrast, averaged 177 days.

State leadership shapes efforts—or lack thereof—to address learning loss

Rhode Island was the only state in the region that required districts to submit evidence of a plan to assess students’ learning progress and loss, including multiple forms of assessment. Massachusetts brokered access to diagnostic assessment tools at no cost and encouraged districts to take advantage of them.

Even with these state measures, only around half (43) of reviewed district plans referenced using diagnostic tests or formative assessments to measure students’ learning needs, and just 34 discussed using such assessments throughout the year. Vermont districts were least likely to mention diagnostic assessments.

As for evidence-based strategies to address learning loss, only 15 districts made clear reference to tutoring as part of their plans.

This could be a warning sign that school systems are not systematically tracking students’ learning needs and acting to address them over the course of pandemic-related disruptions. It also suggests that assertive state leadership can play a critical role in driving some aspects of school district responses.

We will continue to explore the relationship between state actions and improvements on the ground as we delve deeper into the dynamics of the region.

Think forward, New England

Our research is just beginning. In the coming months, we’ll dig deeper into district reopening plans, hearing from families and educators about their experiences this fall, exploring innovative high schools, and talking with system leaders working to reimagine district operating systems in response to the unprecedented challenges presented by the pandemic. Insights from those who blaze new trails and solve this moment’s essential problems will be invaluable to educators and educator leaders navigating our current crisis. They will also be essential to building a stronger and more resilient school system in the future.

Voice and choice: New England students highlight which pandemic-era changes should stay—and which should go

Lisa Chu

Research AnalystMaddy Sims

Center for Public Research and Leadership