According to a new analysis of state reopening plans by CRPE and Public Impact, states have largely ceded their role in defining how school systems must address the COVID-19 pandemic.

To be sure, these plans offer recommendations and questions for school system leaders to consider. Many plans suggest measures to protect the health and safety of students and staff, such as masks, changes to facilities to support social distancing, and enhanced cleaning protocols.

But on the issues that matter most for student learning—including access to instruction in the face of building closures, action on the digital divide, and plans to address student learning loss—states have typically deferred to local districts. The absence of clear expectations is certain to contribute to inequities across school and district responses.

With a large fraction of American students—if not all—expected to learn remotely for at least part of the upcoming school year, states must step in to address the gaps in learning students experienced last spring, avert a worsening educational crisis, and help local leaders manage the massive challenges posed by the pandemic.

Too few states act decisively to address gaps in remote learning

Last spring’s closures revealed huge gaps in access to remote learning. According to our analysis of a nationally representative sample of district remote learning plans, just one in three districts expected teachers to provide instruction, track student engagement, and monitor academic progress for all students.

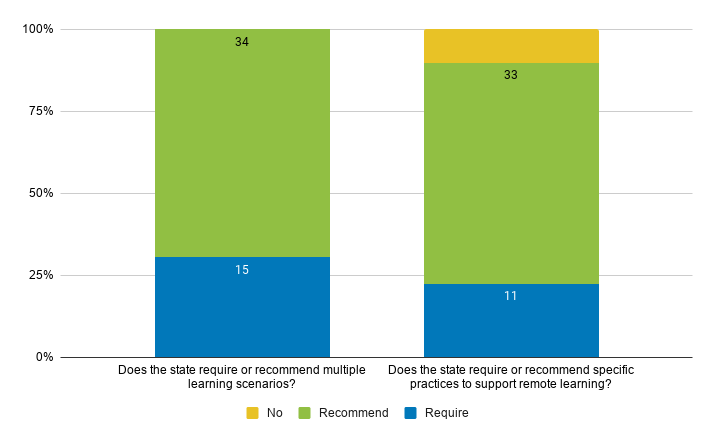

Our first look at state reopening plans suggests too few states have acted decisively to address these gaps. States urged districts to consider multiple learning scenarios (remote, hybrid, and in-person) and often provided resources and recommendations toward this end. But making recommendations won’t ensure that districts adopt a strong plan.

Just 15 states required districts to plan for a remote learning option, and only 11 expect districts to put in place specific practices to support students in remote or blended learning models. Fewer still require specific practices to support students with disabilities (11) or English language learners (7) in remote settings. As a growing number of districts announce plans to open with remote-only instruction, the lack of decisive state action on remote learning is a missed opportunity.

States may have feared they lacked the authority to dictate terms to districts, especially in traditionally local control states, but some states demonstrated they could set clear expectations for the quality of learning models while preserving local flexibility. Rhode Island’s reopening plan requires districts to submit evidence of comparable levels of rigor between online and in-person instruction. In California, the state legislature enacted a variety of new remote learning requirements to address gaps that emerged in the spring. Districts are required to align remote instruction with grade-level standards, provide support to address the needs of students who are not at grade level, and offer daily live interaction with certificated employees and peers for the purposes of instruction and progress monitoring.

Too many states are sidestepping their role in overseeing district reopening plans

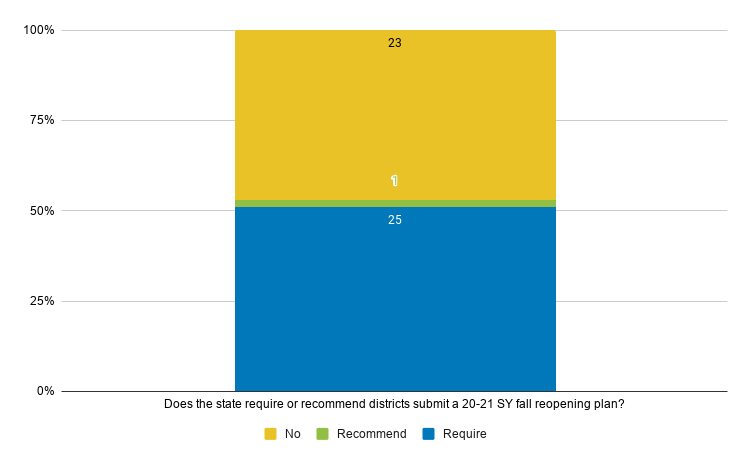

When schools shuttered around the nation last spring, 25 states stepped up to require districts to submit plans outlining how they would continue to educate students in the face of the crisis.

Today, as we look toward a fall filled with more virus-related disruption to public schools, half of states are requiring districts to submit a plan for what happens next; only one in four make it clear that they will review district plans.

To be sure, requiring districts to submit plans is unlikely on its own to solve the challenges for students laid bare by COVID-19. But in combination with clear expectations, a system of support, and continued monitoring, district reopening plans are the foundation for state oversight. Without them, states lack information on how districts are responding to the crisis and make it difficult if not impossible to systematically respond to any gaps that emerge across districts.

Many states aren’t taking concrete actions to address the digital divide

Among the significant barriers holding students back from success this fall is inadequate and inequitable access to devices and internet connectivity. In the spring, the digital divide meant some students lacked access to critical instruction when learning moved to the cloud.

Most of the state plans we reviewed encouraged districts to assess student access to devices and internet connectivity and act to address it. Less common were concrete actions by states to address the digital divide. Florida encourages districts to use their CARES Act funding to purchase education technology. Georgia, among many others, suggests districts survey families to determine how many hotspots and devices are needed. Indiana and Montana maintain a list of low-cost internet providers.

Contrast these efforts with those in Maine, where action by Governor Janet Mills closed the digital divide for students by securing more than 14,000 wifi-enabled tablets and more than 7,000 Chromebooks. Or Connecticut, where the governor’s COVID-19 Learn From Home Task Force launched a statewide survey to assess districts’ need for devices and coordinated the distribution of 60,000 laptops to the highest-need districts. Or South Carolina, which hired an outside contractor to map internet access across the state and passed legislation to provide free hotspots to 100,000 households under the poverty line.

States can have an impact on district plans for addressing learning loss

Projections from last spring suggest students could expect to lose anywhere from one-third to half of their academic gains from last year compared to typical progress—with large racial and class disparities in estimated losses.

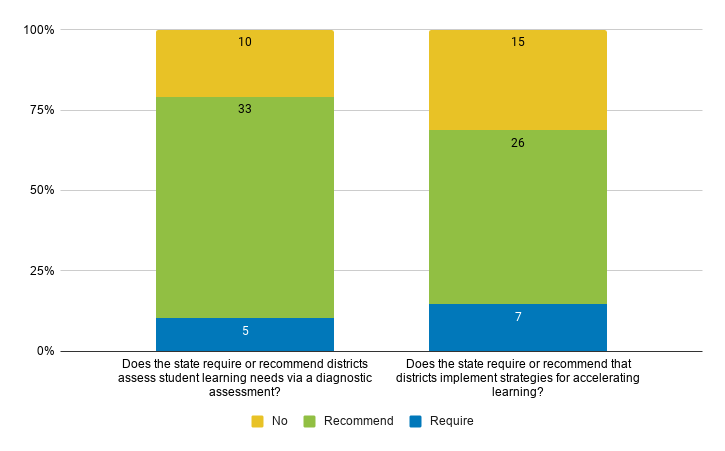

Yet few states appear to require districts to take action on learning loss. Just five have a requirement that districts assess student learning needs this fall via a diagnostic assessment, and only seven require districts to implement strategies for accelerating learning or addressing learning loss.

While a majority of states issue recommendations for districts in these areas, these may not be enough to spur action. In our initial review of district reopening plans, less than a third reference intervention strategies to help students make up learning they may have lost as a result of last spring’s closures. And with achievement gaps estimated to widen by 15 to 20 percent, state requirements to address learning loss could have major impacts on whether districts intervene.

Some states have made addressing learning loss a key priority. Louisiana requires schools to assess student learning needs, offers guidance on how to support “unfinished learning,” and requires school systems to create individual support plans for students needing additional support to reach grade-level standards. Rhode Island requires districts to develop a plan for assessing students’ learning progress and loss and identify an intervention plan for ensuring all students’ needs are met, including multilingual learners and students with disabilities. New Mexico passed legislation requiring districts to add instructional hours to address learning loss.

It’s not too late; states can and must act now on student learning

Last spring exposed widening inequities and learning gaps across schools and districts. Without decisive action from states to address these challenges, this trend is likely to continue this fall. Students whose parents can’t afford to join learning “pods,” those who rely on special education or English language learner services, and other vulnerable students have the most to lose from inaction.

At a minimum, states should:

- Put in place ambitious expectations for remote learning, which looks increasingly likely to be the norm learning modality this fall.

- Give districts a default virtual learning platform with built-in high-quality instructional materials, professional development, and assessments.

- Work aggressively to close gaps in access to devices and internet connectivity.

- Plan to monitor local school systems and step in when students are being left behind.

Governors can and should act to ensure state education agencies can prioritize student learning in the months to come. This may mean mobilizing state public health resources to provide clear guidance to schools so that state education agencies are able to focus on critical issues related to teaching and learning.

In the weeks to come, we will be releasing additional analyses examining how some states are stepping up to address learning gaps for students. This will include deep dives on issues like state virtual instructional platforms, how states are tapping stimulus dollars, and shifts in statewide instructional policies.

It’s not too late for states to step in and push school systems to embrace more effective responses to the crisis.

Bryan Hassel is co-president of Public Impact.

Beth Clifford is a policy analyst at Public Impact.

About our analysis

To create this database, we visited state education agency websites and examined other official directives. We present information for 49 states. We exclude the state of Hawaii because the state administers a single local education agency. The evidence we cite was the best available at the time we conducted our analysis but we realize guidance is changing rapidly. If you have questions, or see information in our database that needs updating, please email us at crpedatabase@uw.edu.