With public health concerns mounting, a growing number of school districts in our nationwide review have shifted their fall plans and are now on track to begin the year fully remote.

Meanwhile, as districts and states grapple with whether and how to bring students back into classrooms, academic planning is getting short shrift and vulnerable groups, such as students experiencing homelessness and English language learners, appear to be especially shortchanged in district planning.

Districts and states are shifting toward fully remote reopenings

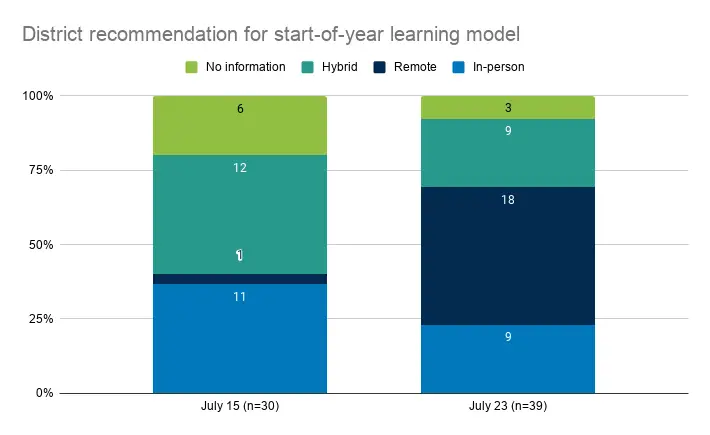

Districts have made a rapid shift away from in-person instruction. Last week we reported on 30 district reopening plans and this week we have added 9 more; a growing number of districts indicated they do not plan to start in-person classes.

Last week just one district—Montgomery County Public Schools, MD—recommended a remote learning model, something they plan to continue through the first semester. Since then, 11 of the 30 districts we tracked last week have changed their preference to remote learning this week. And the majority of the new plans we found—six of nine—recommended remote learning as well.

The challenge districts and states face—keeping students and staff safe while addressing already-widening equity gaps—is unprecedented. There is no easy answer without downsides.

Districts could approach their return to in-person schooling (a clear preference just a week ago) through creative use of spaces, such as setting up more off-site outdoor learning classrooms using parks, sports fields, or unused warehouses. Using these Summer months to set up such partnerships and arrange the space are necessary to implement by the fall.

We have seen few examples of out-of-the-box thinking on alternative use of public and private space. School board members in Seattle suggested an outdoor education plan in collaboration with community organizations and staff. Their plan asks the City of Seattle to dedicate “large swaths” of public outdoor spaces for educational purposes during school hours. However, that proposal may be shelved now. The district’s latest plan, updated this week, calls for starting the school year remotely.

This week’s rapid backpedaling away from in-person instruction at the state and local levels highlights the pitfalls of preparing for learning setups that simply won’t be viable if the virus continues to spread out of control.

State guidance shifts

Districts waited through the spring and early Summer months for lagging state guidance on health, safety, and learning model recommendations. This past week, some state leaders reacted to recent virus surges and federal recommendations with stronger language for schools. But that guidance sometimes shifted quickly, or was out of sync with local contexts, triggering conflict and confusion.

Following the California governor’s recommendation last Monday that large areas of the state return to more restrictive social distancing measures, Los Angeles Unified School District and San Diego Unified School District released a joint statement saying they would open fully virtually. Other districts in California followed suit. Nearby, the Orange County Board of Education released a board recommendation to open schools in-person, in defiance of state guidance.

The Texas Education Agency, meanwhile, first announced that all Texas schools would open in-person while providing a fully remote option. A week later, the agency retracted this requirement and allowed schools to delay on-campus instruction by up to eight weeks.

Similarly, in Florida, following an order from the education commissioner to open in-person, several large districts—including Pasco and Hillsborough Counties in the Tampa Bay region—announced they are considering delaying the start of school while they prepare to offer a mix of fully remote and in-person options.

Other districts have walked back plans to reopen in-person, or have put fully remote learning back on the table. Denver Public Schools, one of the first districts to announce all schools would follow an in-person learning model in June, this past week shifted its plan to fully remote.

Twelve of thirty-nine districts have delayed the start of their school year to continue preparations. During Atlanta Public Schools’ one-week “Runway for Return for Learning” period, staff will engage in family connections, team building, teacher planning and professional development, and safety planning. Staff may hold in-person small-group sessions with teachers and students, give diagnostic assessments, provide social-emotional learning support, and distribute devices during this time.

Districts prepared least for the most likely scenario

Initial plans’ strong focus on health and safety practices and commitment to in-person instruction (either fully or a few days a week in a hybrid model), and relative lack of information on remote learning details, imply that districts may have spent most of their Summer preparation time on figuring out logistics for returning to in-person instruction and not fleshing out fully remote learning scenarios.

This may not be surprising, given the challenges this spring’s remote learning efforts revealed, many parents’ preference for face-to-face learning, and many families’ needs for childcare as they return to work. However, districts seem to be falling short on providing robust plans for a potential return to fully remote learning, and providing a meaningful continuity of learning experience for students who may wind up transitioning between remote and in-person instruction over the next school year.

This week’s rapid shifts raise the worrying prospect that many districts are now on track for a rerun of this spring: a rush to implement remote learning with just a few weeks to plan for how to do it effectively.

Students and families cannot afford to repeat this spring. To have any hope for a sustainable approach to remote learning, districts must put systems in place that support continuity as students and teachers alternate between remote and in-person learning. They must have options to form partnerships with childcare and online learning providers.

And parents may need options for alternative programs if their districts can’t pull it off.

Districts, likely to experience more learning loss this year, have little in the way of plans to address it

Less than a third of reviewed plans (31 percent, or 12 of 39) reference intervention strategies to help targeted students make up learning they may have lost during spring or summer. Only six districts communicate a plan to provide student tutoring, and just one district communicates information about how it will support high school students with college and career readiness during remote learning.

As remote learning becomes more likely, districts must revisit spring remote learning plans and share concrete details on how students will receive adequate access to high-quality instruction, curriculum, and progress monitoring for potentially a full school year of remote learning.

Of the districts we reviewed, 34 of 39 (87 percent) have used parent and family surveys to gather input. About half of districts—19 of 39, or 49 percent—go further, also explaining that they are using this feedback to shape their fall plans.

Districts continue to provide surprisingly little detail on how they will prioritize their most vulnerable student populations

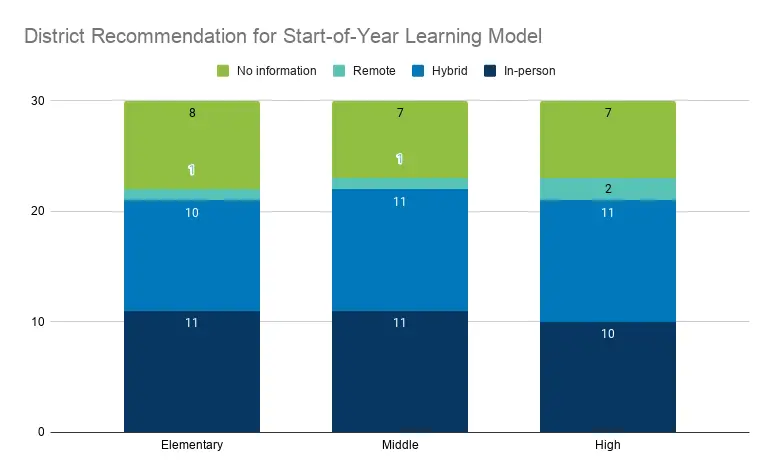

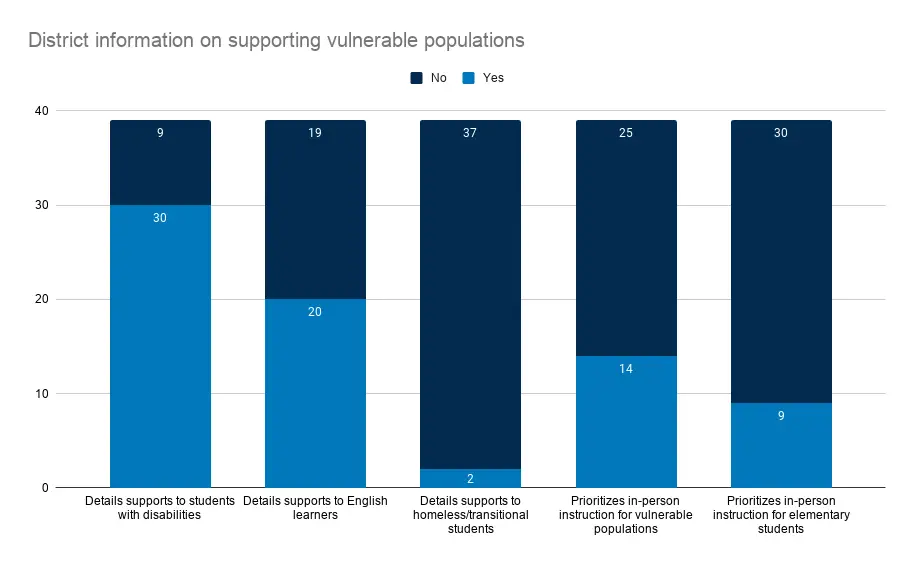

Most district plans make only minor mention of vulnerable populations, such as students with disabilities, English language learners, and other learners who need additional support. Of the fall district plans we’ve reviewed, only 36 percent (14 of 39) of district plans prioritize in-person instruction for vulnerable populations.

Of the 39 district plans we reviewed, 30 (77 percent) mention supporting students with disabilities. Twenty plans (51 percent) mention English language learners, and only two mention homeless and transitional students. In all but a few plans, there is very little detail about these groups. Milwaukee Public Schools has a detailed student support section of their plan. The district outlines a process for identifying and supporting vulnerable populations, which also includes thinking creatively about different roles of paraeducators and rethinking co-teaching.

This spring, students with disabilities and other vulnerable populations were often overlooked. Too many students were not able to access the remote curriculum—due to connectivity gaps, language barriers, lack of training on technology, lack of appropriate accommodations and modifications, and lack of support. Some students struggled with the change in routine. Some could not fully understand that the virus was the reason for this change of routine. Others did not have the executive functioning and attention skills to attend online.

As a growing number of districts lurch toward remote learning, they must prioritize the students who had the fewest learning opportunities this spring. Our school systems must not allow them to be left behind a second time.