Student enrollment is falling at public schools across the country, impacting funding streams and threatening financial solvency, as schools continue to be on the hook for considerable fixed costs like loans or debts. Having to pay out teacher pensions (mostly using current revenue to pay retired teachers) is contributing to this growing problem. But even though teacher pension plans are tremendously expensive, they’re still not serving the majority of their members. There are better ways to provide benefits in a more sustainable way.

Nationally, teacher pension costs amount to around $83 billion a year, or about one out of every ten dollars that taxpayers provide for public education. That works out to almost $1,700 per student.

These pension payments are eating up a growing share of the funds that taxpayers think are paying for teaching and learning. This millstone weighs down districts and hampers their ability to be responsive and flexible to falling enrollment levels or other changes in student needs.

States and districts are contributing nearly 20% of each current teacher’s salary toward pension costs. That figure is much, much higher than what a typical private-sector employer pays toward retirement benefits and does not include Social Security contributions.

High pension costs might be worth it if they accomplished some greater purpose, like boosting teacher recruitment or retention efforts. But the best research suggests that teachers would prefer to receive more of their compensation in the form of higher base salaries.

Compounding these issues, teacher pension plans are not even delivering good benefits for most of their members. The plans have accumulated billions in “pension debt,” which now consumes about 80% of all the money going into the teacher retirement system. While employer contributions into the plans have quadrupled over the last two decades, states have cut benefits for new teachers by raising retirement ages or reducing benefits in other ways.

Those reductions will exacerbate a system of extreme winners and losers. Some long-serving veteran teachers will draw down such lucrative benefits that they are essentially “pension millionaires.” Meanwhile, the vast majority of workers—who may only stay for 3 or 5 or 10 years in a given plan—will leave with no or meager benefits.

As a result, school districts are fighting for talent with one hand tied behind their backs. Rising pension costs have left them with less discretion over their budgets. They also have no control over either the benefit structure or contribution rates, and they can’t compete for talented workers with other school districts in their state because they all offer the same retirement package. Worst of all, the benefits they do offer are unattractive to younger teachers who aren’t willing to commit upfront to a 20- or 30-year career.

The problems on the benefit side are comparatively easy to solve, at least from a technical standpoint. There are a variety of models from both the public and private sectors that do a better job of keeping costs at a reasonable level while also providing solid benefits. Public higher education, for example, offers much better benefits than those K-12 teachers receive at a fraction of the cost.

In contrast, there are no easy solutions on the cost side, and the debts will have to be paid. But policymakers in too many states are ignoring the problem and praying that rising equity markets will somehow save them. This ostrich-like approach has proven ineffective, and state leaders need to recognize that their current plans are both costly and failing to provide for too many workers.

The financial problem

Teacher pension plans don’t work like defined contribution plans. Under 401(k) plans held by private-sector employees (or 403(b) plans, for nonprofit employees), retirement accounts grow with employee contributions, plus employer contributions and investment earnings. Pension plans shield their members from all of that. The state sets contribution rates, and members qualify for benefits based on formulas tied to their salaries and years of service. In a well-managed pension plan, the value of the benefits should roughly equal the value of the contributions into the plan over time. In teacher pension plans, however, there’s been a growing disconnect between the value of benefits that workers receive and the amount of money that employers have to put in.

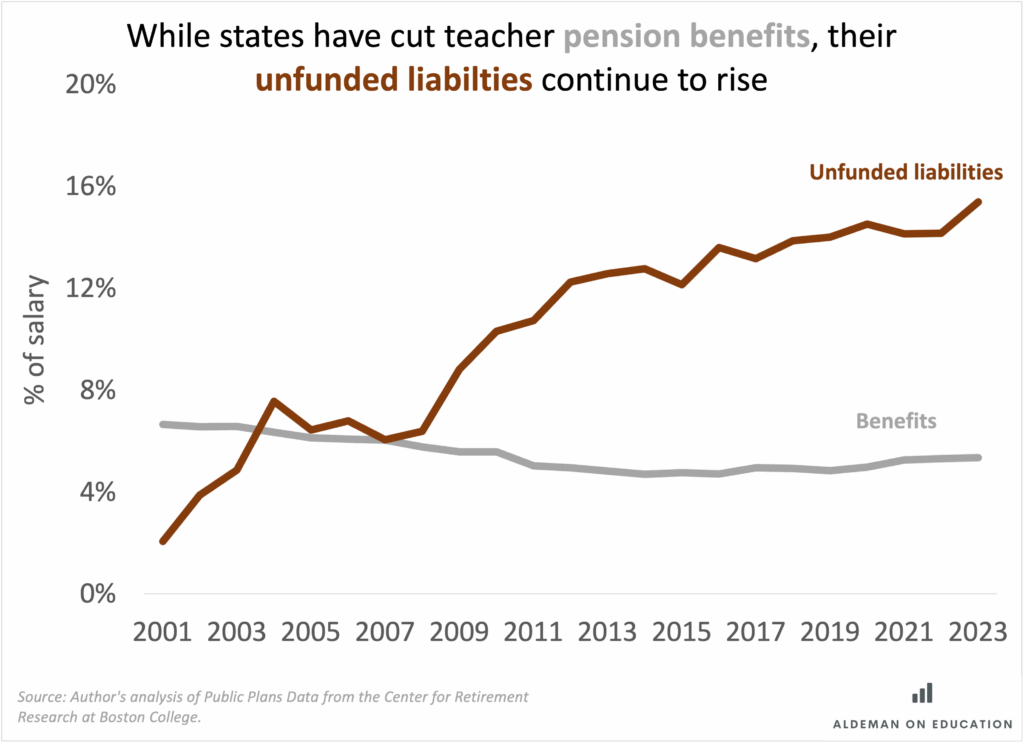

The chart below separates teacher pension costs into two buckets. The value of teacher pension benefits (in gray) reflects an average across all members. Over time, the value of teacher pension benefits has fallen from 6.6% of salary to 5.3% of salary. To put that in perspective, an employer in the private sector might make a 3-5% contribution toward a typical 401(k) plan. In that sense, teacher pension benefits are—on average—relatively generous but not extraordinarily so.

But now look at the red line. That’s how much employers—states and school districts—are paying toward unfunded liabilities. Those contributions rose from 2.1% of salary in 2001 up to 15.4% in 2023.

To be clear, the $708 billion in “unfunded pension liabilities” are essentially promises owed to current and future retirees. That debt doesn’t have to be paid back all at once, but thanks to ironclad legal protections and political realities in most states, the benefits will eventually have to be paid. For now, states and school districts have less money to spend on raising teacher salaries, responding to enrollment declines, or any other priorities.

The benefit problem

Remember that the value of the average benefit is only about 5% of each teacher’s salary. This masks wide disparities within the education workforce. In a typical state, a worker’s benefit is based on their final salary (over their last three to five years of their career) multiplied by their years of service and some “multiplier,” say 2%. As one example, consider a 60-year-old with a final salary of $80,000 after 25 years of service. Their annual benefit would work out to:

$80,000 salary x 25 years of service x 2 percent multiplier = $40,000

While this may seem straightforward, there are some key nuances. The first is that workers can’t start collecting full benefits until they reach the “normal retirement age,” which in some states might be the teacher’s early 50s, while in others it could be as high as 67. Researchers have found that whatever the age is, it acts as a strong anchor for teachers who are close to retiring. That is, the pension plans do a pretty good job of keeping 59-year-olds if they know they can retire with full benefits at age 60, but they also gently nudge out 60-year-olds who might still be enjoying productive years in the classroom. Other research has found, however, that these anchors are quality-agnostic, and pensions have the same push-and-pull effects on great teachers as they do on poor ones.

The benefit formulas have some other quirks. One is that the salary component is based on the employee’s salary in the last years they worked. That is, if someone teaches for 25 years and then decides to care for a grandchild at age 50, they can’t collect their benefits right away. Then, when they start to collect their pension at age 60, the dollar amount is still based on the salary they’d been earning when they stopped working 10 years prior. In contrast, someone who hits the same 25-year service threshold right as they turn 60 receives a larger benefit, simply because it’s calculated based on their present-day salary.

This is a significant problem for people who start teaching in their 20s and 30s. If they serve for 5 or 10 years before moving on to another role, or if they take a teaching job in another state, then their benefit slowly wears away to inflation. As a result, someone who splits a 30-year career over two states will receive 50-75% less in benefits than someone who stays in a single state for their entire career.

The vast majority of teachers get very little value from their pension plans. Some long-serving veterans will eventually earn a benefit that’s worth much more than the average. Depending on the state, about 20% of new teachers will win the pension lottery. But that means 80% of new teachers lose out.

Teachers with higher turnover rates are more likely to be on the losing end. That includes charter school teachers, special education teachers, and math and science teachers. Black and Hispanic teachers in urban areas are also less likely to qualify for the most generous pension benefits. The prospects are worse for non-classroom roles like instructional aides or bus drivers, who tend to have much higher turnover rates than teachers but are often in the same “teacher” pension plans.

The solution

When an oil well leaks, the oil company has to cap the leak and clean up the spilled oil. Pensions have similar challenges. States need to stop adding to their pension debts, and they need a responsible plan to pay off those debts over time. Fortunately, the solutions to the two problems go hand in hand.

First, they need to stop adding new workers to their current plans. Instead, states should create new, portable benefit plans for all incoming workers. The simplest option would be a defined contribution plan like a 401(k). In fact, many states already offer their public higher education workers access to 401(k) plans with superior retirement benefits to what their K-12 teachers have.

Another option would be cash balance plans. These are legally defined benefit plans, like pension plans, but they guarantee employees a modest rate of return on their investments rather than using the benefit formulas discussed above. Account balances grow steadily over time, and employees can be confident that their nest eggs are protected from the volatility of the stock market. Over 10 million workers are enrolled in cash balance plans, including those at companies like IBM and FedEx, as well as county and municipal employees in the states of Texas and Nebraska, as well as teachers in Kansas.

Both 401(k)s and cash balance plans are fully portable and don’t backload benefits the way traditional pensions do. Moreover, states could convert account balances into annuities at retirement, which would offer predictable monthly payments to retirees just like traditional pensions.

Closing off the existing plans for new members would give state leaders the space to plan for how to pay down their current obligations. But states, not schools or districts, should own that liability. Right now, 36 states put some or all of the burden of unfunded liabilities on districts. That’s not fair. After all, former legislators and governors were the ones who made the decisions that led to the current piles of debt. Moreover, states have a bigger and broader tax base to pay down those obligations than districts do. The pension bills won’t go away just by shifting responsibility for who pays them, but it should be the state government that bears the burden.

Without taking action, pension costs will continue to eat up larger shares of school budgets. That, in turn, will make teaching less attractive to new entrants and preserve a benefit structure that protects only the longest-serving veterans. State leaders must take action to attract a truly vibrant educator workforce and ensure their investments in schools actually make their way into classrooms.

Grounded in CRPE’s core belief that public education is a goal, not a particular set of institutions, this series begins with exploring what shape a revamped federal role in education might take. Future posts will examine the evolving responsibilities of states and local communities. This series is a forum to challenge assumptions, spark debate, and generate ideas for preparing today’s and tomorrow’s students for a rapidly changing, uncertain future.