This piece was originally published on The 74.

Dusseault & Lee: Other than Hawaii's, no education department has publicly focused on policies governing artificial intelligence in the classroom.

Developments in artificial intelligence technology have exploded into the mainstream this year and welcomed people to summon text, audio and images with a few user-friendly AI prompts. The technology is rapidly evolving and poised to reshape functions of government, society and schools. But most state education departments have not publicly acknowledged this new breed of AI, or the considerations for using it in teaching and learning, according to a national review by the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

CRPE sought to catalog initial responses about AI and its future in education by searching all U.S. state and territory education department websites for related policy guidance or key mentions of AI developments. This data presents an early picture of the AI education landscape and issues states and districts may face in 2023-24.

In May, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Educational Technology released its first report on the subject, which presented the “opportunities and risks for AI in teaching, learning, research and assessment based on public input.” Since then, students, teachers, parents, journalists, podcasters and even teachers unions have discussed AI and ChatGPT. But few state education agencies have offered information on their websites about artificial intelligence and its implications.

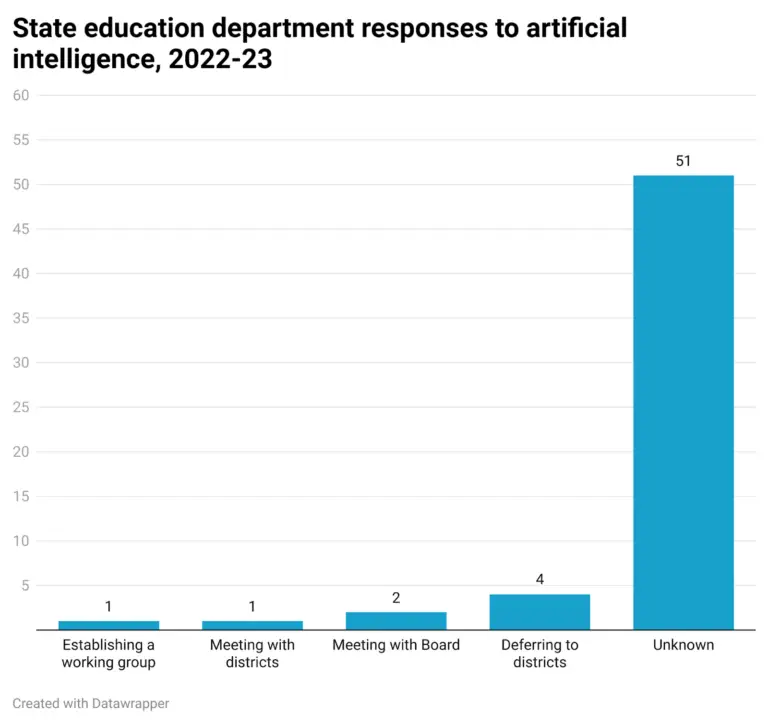

Apart from the Hawaii state Department of Education calling for a working group to recommend uses of artificial intelligence and assistive technology in the upcoming school year, none of the other 58 departments appear to have mentioned AI in a policy context, according to our search of publicly available information.

Seven states have explained how they are, or are not, planning to weigh in on AI-related education issues. The remaining 51 education departments do not appear to have published any details on plans for setting policy guidance around AI.

At least four states said they’d leave the matter up to individual districts. A spokesperson for the Iowa Department of Education said decisions about academic expectations, honesty and whether to block certain websites or tools are made on the local level. Officials from New York, Rhode Island and Wyoming spoke of similar approaches.

At least two other state education departments have discussed AI with their respective boards. Massachusetts Commissioner of Education Jeffrey Riley said he plans to “bring information” to the governing body “about the impact of technology, cellphones and other devices and artificial intelligence on education.” But he did not indicate whether he wishes to propose regulations governing the use of AI in schools. Frank Edelblut, New Hampshire’s education commissioner, gave a presentation about ChatGPT to the state board of education and called for “updat[ing] our models for the 21st century.”

In Idaho, state officials indicated in May that they were starting to talk with districts about AI in schools.

About half of the departments, 30 of 59, have made at least a key reference to AI on their websites since last August. But just Georgia, Florida, South Carolina and Arkansas have posted curriculum standards and/or courses that would teach pertinent concepts. All four states started that work ahead of the last school year.

In 2021, the Georgia Department of Education updated its career, technical and agriculture standards to include an AI pathway. The state now has a sequence of three courses that study AI foundations, concepts and applications. One district, Gwinnett County Public Schools, opened a high school last year that aims to provide students with a college preparatory curriculum taught through the lens of AI.

In March 2022, Florida’s State Board of Education approved an AI curriculum framework and partnered with the University of Florida to develop and provide districts with professional development, coaching and resources. This includes a new, three-year “AI Foundations” course of study in its career and technical education program. Last summer, university students and faculty led free workshops for teachers from 11 districts and the Florida Virtual School to prepare them to teach AI. Training will occur annually until 2025, with four new districts added each year.

In April, South Carolina’s education department sent a memo to superintendents, administrators, instructional leaders and teachers about plans to adopt a statewide framework for AI. Officials are soliciting feedback on the draft standards.

Arkansas adopted a three-course artificial intelligence and machine learning pathway in 2020 as part of a broader update to its computer science standards and courses. Unlike other states, it has not recently updated those courses, but it’s providing six days of professional development on them this summer for high school teachers.

AI’s potential to reshape and disrupt longstanding habits in teaching, learning, assessment and management has yet to fully develop. CRPE’s reviews over three years of pandemic-era schooling have found that in moments of crisis or ambiguity, states often refrain from providing critical, proactive guidance that can help districts navigate uncertainty. Similarly, large school systems can delay their responses in critical moments, which can have detrimental consequences for students. We’ve seen beneficial results when states offer early guidance. For example, a handful directed federal COVID relief funding priorities toward practices that advance equity. Connecticut was one of those states, and its subsequent spending on evidence-based strategies helped increase student attendance.

The few states that moved early on AI training, curricular guidance or new course options — even before the advent of ChatGPT — may be better positioned to support districts addressing concerns and opportunities sparked by the technology in more accessible, equitable ways.

If states can prepare guidance or policy suggestions ahead of the 2023-24 school year, they can better safeguard and more equitably prepare students to learn, live and work in an increasingly technology-driven society. They can also assist districts that have not yet focused on AI because they are prioritizing pandemic student recovery needs and/or workforce shortages instead.

Departments could consider: 1) establishing guardrails to protect against inherent bias in AI; 2) providing guidance that anticipates inequitable or inconsistent student access; 3) offering professional development that helps teachers and school leaders adapt to new tools and practices, 4) establishing plans to measure and track the effectiveness of AI-enabled supports for student learning; and 5) examining the pros and cons of tools that could reduce teacher workloads by automating mundane tasks. Districts would benefit from state leaders looking further down the road and evaluating curricular options, examining the quality of AI products and assessing the opportunities and risks to widespread integration of artificial intelligence in schools.