Twenty-five years ago CRPE was founded on the idea of the school as the locus of change. Today we are reexamining our old assumptions in light of new technical possibilities, changes in the economy, and a recognition that even the most effective schools may need to develop new approaches to better serve students whose needs warrant more individualized learning pathways or supports. This post is part of a series on what the school or learning system of the next 25 years might look like.

Educators throughout New Orleans’ decentralized school system tend to fixate on numbers. How much academic growth do their students make in a year? How do their proficiency rates compare to other schools around town? Will they attract enough students to balance their budgets next school year?

One of the city’s newest school leaders, Jonathan Johnson, is focused on a different number: 228. It’s emblazoned on banners hung on the walls of Rooted School. It’s on Johnson’s mind when he walks the halls, or travels out of town to recruit donors, college partners, or companies where he hopes his students will one day land tech jobs. That number, 228, represents a widely publicized estimate of the number of years it will take black Americans to close the racial wealth gap with white Americans if present trends continue.

That’s the number Johnson has set out to change. He wants to equip Rooted’s students to close that gap within their lifetimes. One of those “228” banners hangs on a wall, surrounded by printouts of contracts signed by each student. They pledge that by the time they graduate, they’ll have earned at least one professional credential, and acceptance to at least one college.

“We exist to provide our students multiple pathways to financial freedom,” Johnson said.

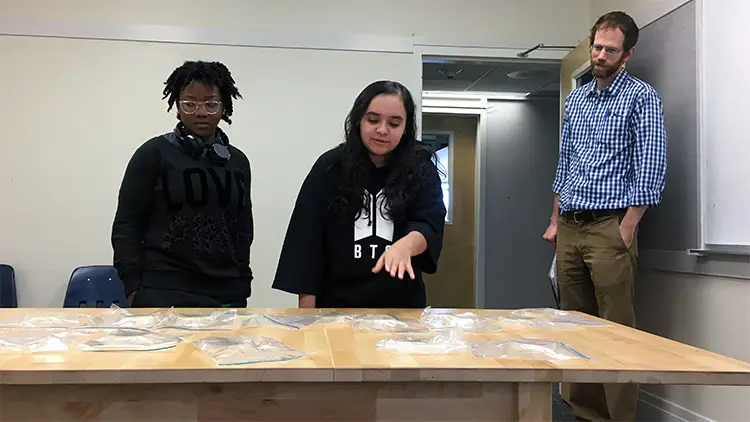

Science teacher Ryan Fuller joins tenth graders Saidi Zelaya and Soad Martinez as they inspect bacteria cultures.

To provide those multiple pathways, this startup of 90 9th and 10th graders challenges many of the conventions of public education. Students take two online classes to meet their state graduation requirements. Rather than taking traditional high school electives, they spend two hours a day in a technology block where they work on mastering skills that lead to industry certifications. Each year, Rooted aims to have a quarter of its students working in part-time internships. The goal is to build relationships with employers in the burgeoning “Silicon Bayou” tech scene and to initiate a two-way learning process. Students will learn how to work in tech jobs. Employers will learn that, as Johnson puts it, “By working with us, you have the capacity to develop homegrown talent.”

Like many New Orleans educators of his generation, Johnson felt called to teach here. He grew up in Southern California; when he was in the 5th grade, his family fell behind on mortgage payments and had to move. Later in life, he resolved to make sure his family—and others like them—would never lose their foothold on the American Dream. When Johnson was in high school, he was moved by TV footage of Hurricane Katrina survivors fleeing for their lives in neck-deep waters, and the institutional racism exposed by the failed disaster response. The images motivated him: upon graduating from Chapman College he signed up for Teach for America and listed New Orleans as his first-choice assignment. Johnson took his first teaching post at KIPP Central City.

It was there he saw firsthand that for some students, education can be a race against time. Four years of high school followed by four years of college provides a wide window for tragedy or one of life’s disruptions to throw an education off track—a reality behind the statistics that say students growing up in poverty face long odds of finishing college. This point was driven home for Johnson when one of his 8th grade students was murdered.

At Rooted, Johnson describes a broader mission. Many schools that took root in post-Katrina New Orleans hew to a formula focused on high expectations, strict discipline, and strong academics. They propelled undeniable gains in student learning. But Johnson says they have yet to transform the quality of life for the families they serve, or break down the racial and socio-economic barriers that continue to divide the city’s students. He wants to find new school models that can appeal to families of all backgrounds by catering to universal aspirations like, We can help your child land a job at Google.

When I visited, I saw students carrying laptops from one room to another, collaborating on assignments and trading teenage banter. When they knocked out assignments quickly, some students would take a break with a round of Super Smash Bros. Others would head down the hall to check on a science project, where bacteria samples taken from around the school building were starting to blossom in petri dishes.

A 10th-grader, Dorian Hunter, was perfecting a model of the Superdome for his capstone project. Students are required to build a replica of The Game of Life board game, set in New Orleans during a period sometime in the past or future. The projects require them to research technological and cultural trends, climate change, and historical events—and also to demonstrate their 3-D modeling skills. Among other things, students must precisely measure their game pieces to replace the plastic components of an existing Life board, which requires them to adapt the measurements to their own designs. In short, the project helps integrate skills from multiple subjects, while also helping students build their technology skills.

More than four-fifths of Rooted’s freshmen earned web design certifications last year, and they’re expected to add new credentials each year, sampling data science and cyber security before pursuing advanced credentials in a chosen specialty.

Still, integrating core subjects with job skills hasn’t been easy. Johnson said his school constantly butts up against systemic constraints—credit hours, seat time requirements, courses of study—that don’t line up with all the things graduates will have to know to thrive in a world beset by growing economic inequality and rapid technological change. He wants Rooted students to meet all the requirements that would allow graduates to claim Louisiana’s TOPS tech diploma designation for those who earn career credentials, as well as the state’s TOPS University diploma for those who complete college-prep academic coursework, while still making room for internships, apprenticeships, or other career-specific training.

By building an entire school around technology skills, Johnson is challenging what some scholars have called the grammar of schooling—stubborn features of public education like the subjects schools teach, course schedules, credit requirements, or the delineation between high school, higher education, and career training. He says a business leader from Indianapolis, where his school is working to launch a second location, has borrowed a term for this problem from the world of computer programming: the “object set” of education is wrong.

Tenth-grade students ask questions during a two-hour technology block.

At the same time Johnson also sees the school battling deeper cultural assumptions about what kinds of instruction can successfully educate low-income students in New Orleans, and whether it’s possible to help students acquire specific skills that will help them land jobs immediately while also arming them with the most important quality they’ll need to attack the number 228: adaptability. When technology evolves, or the economy changes, today’s students and their skill setsf will likely have to change, too.

These battles are still in the early stages. But they raise some issues about the public education system as a whole.

Inequity at home. In an interview, Rooted 10th-grader Jahiron Pandy said students often needed to connect to the internet at home to finish class assignments or complete remote coursework. This created obstacles for some students who didn’t have adequate internet connections or home environments conducive to schoolwork. Some teachers encouraged students to go to libraries or even gave students portable wireless hotspots—a testament to their dedication, Pandy said. As technology allows more students to break free of time constraints that limit their schooling, this highlights a potential out-of-school driver of educational inequity.

Challenging systemic bias. In Rooted’s 10th grade technology lab, boys outnumbered girls by more than two to one. On the other hand, during two visits I saw multiple instances of female students working with supportive peers and filling leadership roles—on project teams and as “student teachers,” a role in which a few select students help pick teams of students that collaborate on assignments, provide feedback on planned class projects, and help peers troubleshoot problems if they struggle with a task. Johnson noted that systemic biases can dampen girls’ pursuits in math, science, and technology fields long before it’s time to choose a high school. This suggests a challenge that may need to be addressed in middle or elementary schools, and could deserve attention from people trying to govern an education system in which students are free to choose specialized pathways tailored to their interests. Who should be responsible for spotting signs of systemic biases, investigating their causes, and correcting them?

A climate of education innovation. Johnson was an educator who saw a problem and hatched an idea for a new kind of institution that would try to solve it in new ways. In New Orleans, he had access to an incubator that let him test his model in a small format and begin building trust with families. Another school was willing to share space with his startup. Post-Katrina reforms turned New Orleans into a magnet for motivated people who cared about improving education. They also created an environment where they could turn their ideas into new kinds of schools, and know students in the city will have equitable access to them.

Old challenges persist. Right now, Rooted operates out of a synagogue in New Orleans’ Uptown neighborhood. But as it grows it will likely need to find a new home. Familiar challenges from the first era of reforms—like charter schools’ difficulties obtaining facilities—will still demand solutions in the future.

Rooted students all read a book that inspired Johnson: Seth Godin’s What to Do When It’s Your Turn (and it’s always your turn). The book finds a common thread between Shirley Chisholm’s longshot presidential bid and the efforts of technology entrepreneurs: risk-takers don’t necessarily need to succeed in order to change the world. Johnson says he still doesn’t know if his startup will succeed. But he hopes it can help widen the window of possibility in public education