As districts move to offer more in-person learning this spring, many teachers, parents and students remain hesitant, worrying whether schools — and their specific campuses and classrooms — are safe. This is especially true for families of color.

In Los Angeles, less than a third of surveyed families plan to return in person. But officials have expressed hope that communicating about district plans, including school-based COVID testing, improved ventilation systems, contact tracing and teacher vaccination sites, will help convince more parents to send their children back.

Our review of 100 urban and large districts finds that many are taking steps to reassure families — such as presenting clear information on virus infections — and most are moving forward to facilitate vaccinations for teachers. But the standards that guide reopening decisions are unclear, and most of the districts lack robust COVID-19 testing programs.

The 2020-21 school year is heading into its final quarter. If districts take increased steps now to protect their students and staff from the virus, and assure the public they are doing so, they could reduce hesitation to return to classrooms and lay the groundwork for a successful start of school in the fall.

Source: Based on CRPE’s analysis of 100 school districts’ publicly available information.

As more districts reopen, clear reporting on school-level transmission of COVID-19 builds public confidence that classrooms are safe. Seventy-eight percent of reviewed districts post daily or weekly updates that detail COVID cases. Aurora Public Schools in Colorado, for example, reports positive tests and exposures as they occur at each school site, as well as the number of students and staff exposed and any actions taken, such as short-term building closures. San Diego Unified School District’s data dashboard shares the number of students and staff tested, as well as positive cases over time.

But most districts do not make clear how community health conditions guide their reopening or closing decisions. Only 6 percent of districts in our review communicate school-level benchmarks for this purpose, while 28 percent communicate benchmarks at the district, but not the school, level. But two-thirds don’t communicate any criteria for future reopening or closure decisions.

Source: Based on CRPE’s analysis of 100 school districts’ publicly available information.

Districts might look to the example set by North Carolina’s Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools, which shares how public health indicators inform decisions about in-person instruction via metrics like the rate of community infections and the percentage of positive COVID tests. The district opened remotely in September and has transitioned into and out of hybrid learning twice as a result of these guidelines.

Likewise, Maryland’s Prince George County Public Schools, still in remote learning, will use specific guidelines (percentage of positive tests, new cases, average daily case rate) to phase in small-group instruction by grade level and for designated populations of students (e.g., special education, English learners) when thresholds are met.

Parents have a right to know what benchmarks will guide districts’ future reopening and closure decisions. By setting clear criteria and communicating them publicly, districts can convey to the public that they are grounding their decisions in the best available data, not bowing to political pressure.

Communicating public-health benchmarks is only one facet of the efforts districts need to take to build the public’s trust in safe reopening. They should also detail the measures they are taking to prevent infections in their schools.

One example would be a regular, robust testing program — at a minimum, of random samples of students. Transparent reporting of test results can also help districts communicate to students, families and staff that their schools and classrooms are relatively safe.

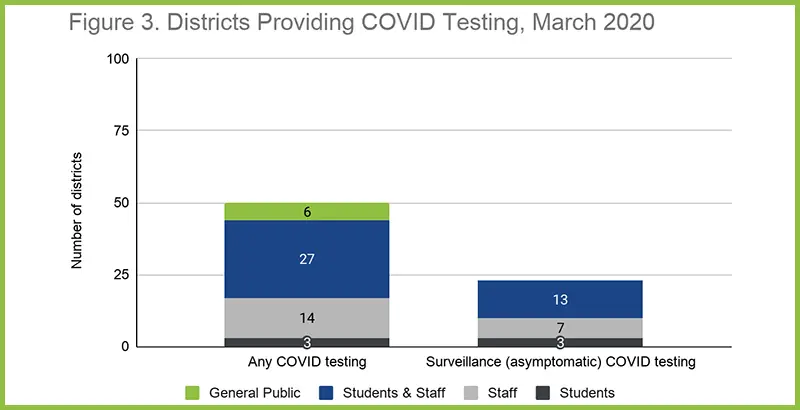

Source: Based on CRPE’s analysis of 100 school districts’ publicly available information. Note: “Any COVID testing” refers to access to testing, but includes testing of probable cases or individuals who self-select, such as when they have symptoms. “Surveillance (asymptomatic) COVID testing” refers to specific programs to test all individuals or a random sample of individuals to better detect COVID spread within school buildings

Just half of districts reviewed provide access to COVID testing for students and staff. This includes testing of probable cases or of individuals who self-select, such as when they think they have symptoms. About a quarter (23 percent) conduct surveillance testing of students and staff to surface and prevent COVID spread. Some of these districts, such as New York City, rely on random sampling. Baltimore City Public Schools provides ongoing non-symptom testing to all students and staff on campus using self-administered oral swabs.

Texas state officials have required the San Antonio Independent School District to offer in-person instruction since October. The district administers a 24-hour rapid test weekly to students and staff in all schools. About 70 percent of staff participate, and a recent report found in-school transmission has been negligible; at the end of February, the positivity rate registered at 0.8 percent.

Following a record-setting freeze that crippled public infrastructure across the state, San Antonio used the 24-hour rapid tests over a weekend to ensure staff and students were safe to return to school.

“We know people have been in close quarters with family and friends because of the weather, and we want to provide a safe environment when they return,” Superintendent Pedro Martinez told KSAT-TV. The district has since offered testing following spring break.

Clearly communicating vaccination plans, and helping school staff get vaccinated as quickly as possible, may be the most important way school systems can allay health and safety concerns and encourage reticent staff to return to classrooms.

Within a week of the Biden administration’s March directive for states to prioritize teachers for vaccinations, the percentage of states doing so jumped from 63 percent to 80 percent, and the percent of districts in our sample that were coordinating teacher inoculations increased from 46 percent to 62 percent.

Chicago Public Schools hosts vaccination clinics at four sites and operates a website to help school staff schedule appointments. As of March 16, the district reported offering vaccination opportunities to 52,374 employees. It plans to report on actual vaccinations later.

After the state of Texas added teachers as a prioritized group for vaccinations, Arlington Independent School District partnered with the fire department to host a mass vaccination drive at ESports Stadium. Other districts, like Buffalo Public Schools in New York, only referred teachers to a notice about eligibility or access from the local public health authority.

States can encourage more schools to reopen and more students to return in person by encouraging partnerships between school districts and local health officials to target school employees for vaccine drives. About half of districts reviewed (46 percent) leverage a partnership with a health agency or health advisory board to communicate health guidelines, provide COVID tests or vaccines, or analyze district health and safety data.

As vaccines become more widely available, schools can also host community inoculation events. Increasing transparency about staff vaccinations, as exemplified by this simple tracker from Denver Public Schools, can help increase public confidence that it’s safe to return to school.

At the end of the day, parents just want to know whether or not their own child’s school is safe. As more districts move to in-person schooling, scores of families are choosing to remain remote. Districts must take additional steps to ensure the public understands how and why schools are reopening in order to build confidence that the risk of transmission in schools is lower than the risk of students not being in school.

The American Recovery Plan Act requires every district have a safety and health plan in place to receive relief funding. Fundamentally, this is also about trust. Just having a plan is not enough. Clarity, details and mobilizing the right messengers matters too.

Boston Public Schools publishes detailed readiness reports for each building on the district website. The reports allow the public to verify when the district has checked air quality, improved facilities and delivered supplies at each school. Information like this can help reassure families who want their children to return to in-person schooling that the decision won’t place their health — or that of others in their communities — in danger.

The next school year is likely to be complicated, but it will be less so if most children return to their classrooms. With access to vaccination, teachers and principals can focus more on academic recovery and serve as highly trusted messengers to families. Building parents’ trust over the rest of this school year and during the summer will build the foundation for greater and more equitable in-person enrollment in the fall.

This post was originally published in The 74.