The just-signed American Rescue Plan allocates more than $20 billion for school districts to implement evidence-based strategies to address learning loss. This is a win for students across the country. However, it begs the question: How will districts do this?

As more large and urban school districts welcome students back to campus, few are providing public details about how they plan to academically support students after a year of disrupted teaching and learning.

Our most recent review of 100 urban and large districts finds that a small number have reported details this winter about how they intend to diagnose and respond to students’ academic needs during the transition back to in-person classes. Some connect this to data from fall assessments. But we remain largely in the dark about what exactly students can expect to learn and what academic support they will receive for the rest of this challenging school year.

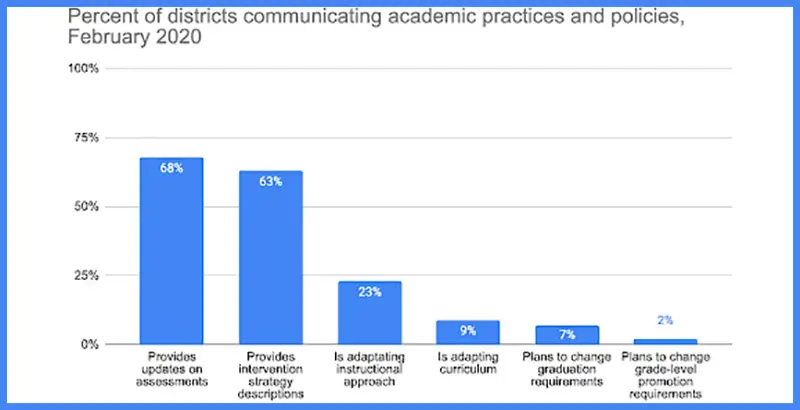

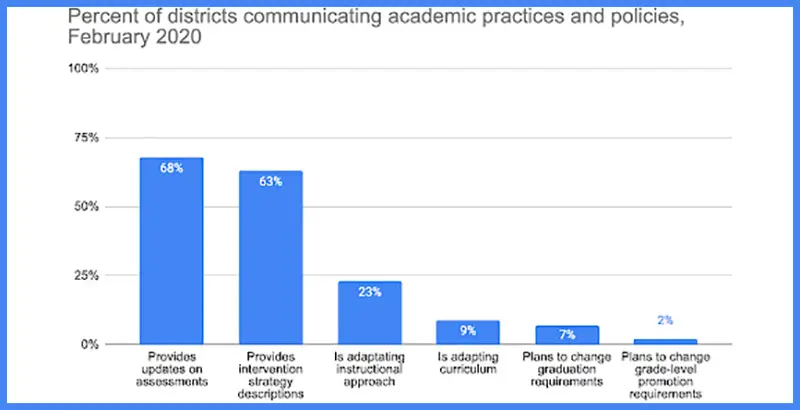

By and large, district communications have prioritized learning model changes and health and safety standards over expectations for student learning. In February, about two-thirds mentioned assessments (68 percent), but plans for using this data to target student support are limited. We have less information now than we did in the fall about what districts are doing in terms of academic interventions. The share of districts providing detail on intervention strategies is down to 63 percent from 66 percent in November.

Twenty-three percent of districts in our analysis have reported they are either providing guidance or professional development for teachers pertaining to remote learning and intervention for acceleration. Districts in remote learning were slightly more likely to explain adjustments to instruction. About a third (31 percent) provided guidance on instructional adjustments to better support students.

Just under 10 percent of districts discuss amending curriculum this year. Some, like Albuquerque Public Schools, are prioritizing standards to focus their academic efforts on essential grade-level content. Others, like Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia, are incorporating more time for social and emotional learning and introducing a more culturally responsive curriculum. These dimensions of education are correlated with academic performance, making them worthy components of learning acceleration strategies.

The wide variation and lack of details underscore an opportunity for policymakers to step in. Just as states set expectations for districts to present reopening plans last summer, they should require districts to report their long-term strategies for helping students address learning gaps and how they will use new stimulus funding to do so. A return to in-person learning is not going to automatically improve on students’ academic and social-emotional well-being.

x0der7adu3c_eznm5dffyqynrp7dltyqqycblluaej5jo_hx0nsuddcm7ch8qhijipu2zq19i3mykpdmexoxypf0ejjq8xgvpe4-vbbm6i7ldgvuv0wfiwrdg6fct1eree5l8pdg.jpg

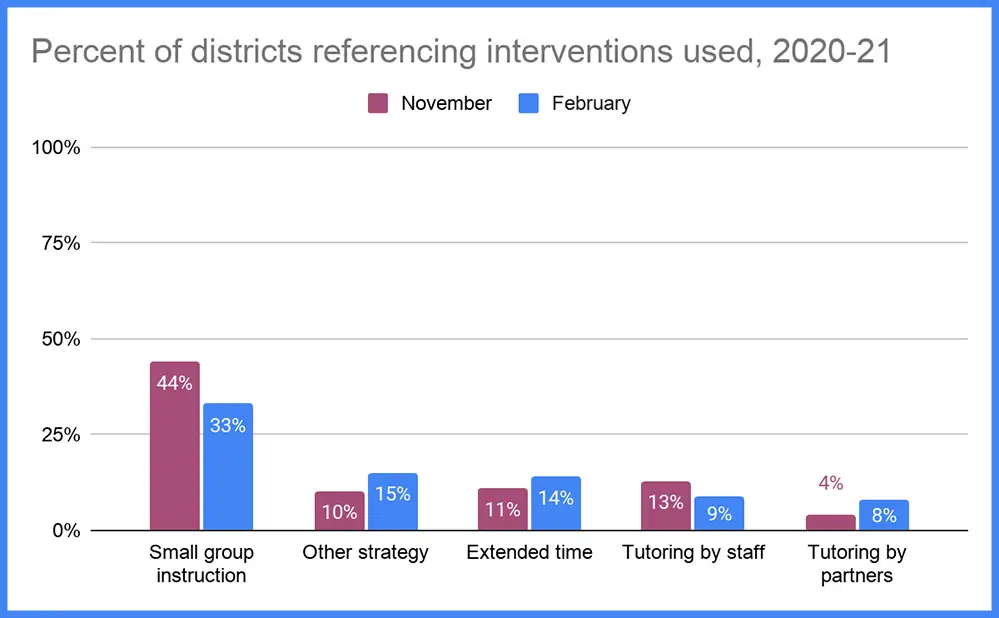

Small-group instruction remains the most common intervention strategy described by districts, but the number that communicated about using it fell by a third (11 percent) since our previous analysis in November. Half of the districts utilizing small-group instruction (17 percent) say they’re using it in tandem with at least one other strategy, such as tutoring, extended instructional time during lunch or on weekends and, less commonly, mentoring, individual instruction and increased social and emotional learning.

Tutoring remains relatively uncommon (used by 17 percent of districts). Among districts that describe tutoring initiatives, a growing number say they plan to work with community partners. This may indicate increased attention to national or statewide tutoring programs, or a way of providing such an academic intervention while freeing up school staff for core instruction and other school-based interventions. Slightly more districts (14 percent) than in our November analysis are communicating extended time as a learning intervention strategy as they look forward to summer school as a way of catching up students.

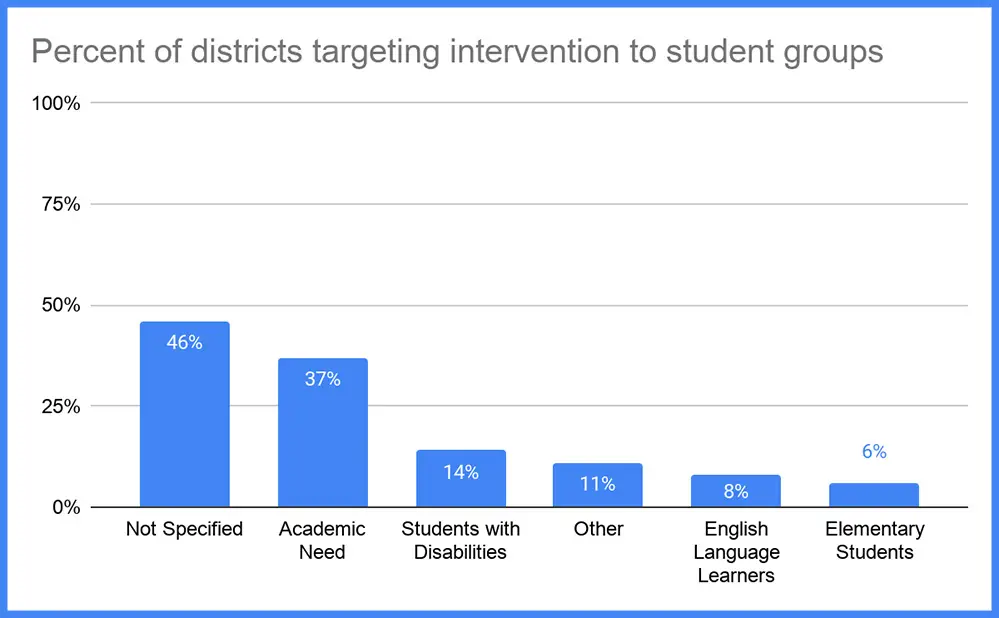

Note: Some districts target interventions to more than one student category.

Nearly half of districts (46 percent) do not specify which students will receive interventions or how they are directing resources for extra support. Of those that do, the most common targeting criterion is students’ academic need (37 percent). Some also consider student characteristics, most commonly disabilities (14 percent) or English learner (8 percent).

Different students will face different gaps in their learning that teachers will need to be equipped to diagnose and address. Nineteen districts in our analysis seem to be taking a business-as-usual approach, using learning intervention plans to support students with no adjustment for this school year compared with previous years. This could be indicative of an existing strong intervention plan, but it would be dangerous to conflate a return to in-person instruction with a return to normal.

But a small number of districts are approaching this year’s disruptions to student learning by relying heavily on data to make strategic decisions about intervention and academic approaches. In a positive example of nimble data-driven strategy shifts, the Washoe County School District in Nevada introduced targeted interventions for high school seniors including counseling, graduation tracking meetings, spring intersession and summer credit-recovery options. The district reported an increase in chronic absenteeism, failed courses and students who were not on track to graduate in time, and responded to the data by launching this comprehensive approach. The district continues to provide interventions to K-11 students but doubled down on seniors based on data that flagged this group as a priority.

When North Carolina’s Guilford County Schools found that fall assessment data indicated that students attending in-person classes the longest performed better than those who had not yet received face-to-face instruction, the district decided to return all students to in-person schooling in February.

Aurora Public Schools in Colorado committed to providing grade-level content throughout remote learning and is using test results in a districtwide strategy to arm teachers with data to understand student progress and encourage schools to use it to tailor academic support strategies.

In some cases, districts are responding to state pressure to make up for lost learning time. The Iowa Department of Education found districts noncompliant if they started the school year virtually for all students, with no voluntary in-person choice. As a result, Des Moines Public Schools added instructional days to the spring calendar, which take the place of previously scheduled professional development days for staff. Students also receive extra instructional time or learning sessions every day through adjusted morning schedules for elementary and middle school students, daily lunch lessons and extended learning sessions after class hours for high school students.

Still, a year into the pandemic, it’s surprising that there isn’t more clarity from districts on what and how students are learning, and how the districts are systematically supporting those who have fallen behind. Districts appear to largely be leaving these details to schools, which inevitably means students’ experiences and the quality of instruction can vary from one school to the next.

Undeniably, teaching and learning have been subject to upheaval, with districts cycling between different learning models since fall. This led to chaotic, rather than consistent, academic interventions. With state-mandated assessments approaching, all districts will soon reckon with lost student academic progress during this COVID-impacted school year. Schools are quickly shifting to more hybrid and in-person learning, more teachers are getting vaccinated and the time to start planning for summer school is coming soon; when will districts start to share more about their core business of ensuring that all students receive the education they deserve?

Given that stimulus funds will soon be flowing, now is the time for districts to make clear whether and how they are approaching lost learning time and using data to match interventions to student needs. Few districts that we studied are yet communicating strategies and plans for making up for learning that many students lost because of the pandemic and continued school closures.

Most importantly, parents are clamoring for more details. As more students return to in-person schooling, they and their families need to know that they are going to be set up for academic success. Districts owe it to families to shore up expectations and communicate their plans for supporting students who have lost time and learning.

This post originally appeared in The 74.