One Saturday morning a few years ago, I was walking through an outdoor market in downtown St. Petersburg, Fla., where I lived at the time, when something piqued my professional curiosity.

A group of homeschool students were showing off art projects. I was trying to get a better feel for the various homeschool cooperatives that were cropping up around the state, so I struck up a conversation with some of the kids. One of them told me they homeschooled through Pinellas County Virtual School.

In other words, while I couldn’t confirm every last detail of their schooling setup as described by a teenager, they may not technically have been homeschoolers. They could just as well have described themselves as full-time public school students taking online classes taught by certified teachers, employed by the Pinellas County school district and paid for by Florida taxpayers.

Perhaps the distinction only mattered in my policy-wonk mind. From their perspective, these families were homeschoolers. Their children took classes in their living rooms, with heavy involvement from their parents, who may have supplemented the official curriculum with art projects they displayed at the downtown market.

But now, as the nation grapples with an eighteen-months-and-counting experiment that thrust tens of millions of families into unplanned at-home learning, I’m starting to think that anyone who’s interested in understanding how this experiment could change public education for the long haul needs to grapple with this definitional issue.

It’s time to embrace an understanding of homeschooling that acknowledges the proliferation of new approaches—virtual schools, learning pods, microschools, “anytime, anywhere” learning, part-time schooling, and more—that blur current definitional boundaries and break down barriers between school, home, and community.

The growing mismatch between family behavior and institutional classification is skewing some efforts to make sense of families’ pandemic-era schooling choices. This spring, the U.S. Census Bureau released survey data suggesting that the share of families who homeschool their children jumped from more than 5 percent to just over 11 percent during the pandemic. Some headlines based on these survey data assert that the number of homeschoolers has doubled.

I’ve suspected something is fishy about these survey data. Families could be reporting their schooling situations to survey researchers the same way those families at the St. Petersburg market reported theirs to me: They count themselves as homeschoolers, when in fact they attend school at home, often virtually.

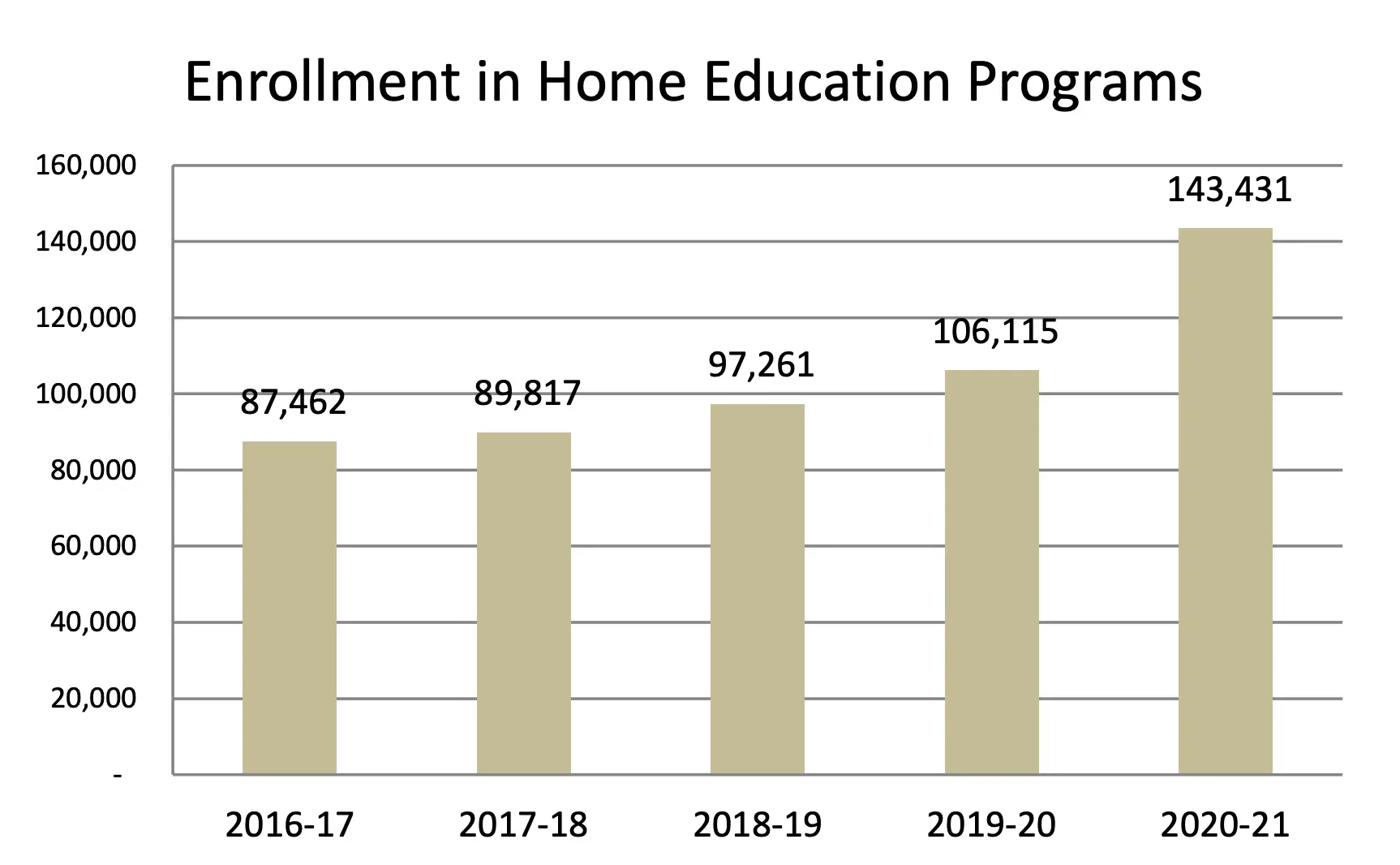

Recently, states have begun to release numbers of students and families actually participating in home education programs. Those numbers show historic jumps in homeschooling but also suggest the Census survey results may have overstated the homeschooling surge. For example, data released this month by the Florida Department of Education show the number of homeschooling students jumped more than 37,000 in a single year.

Source: Florida Department of Education

This 35.2 percent increase isn’t based on parent surveys but an actual count of the students enrolled in home education programs registered with their local school district. It’s a massive increase that could have real implications for public education. But it’s not a doubling. And it’s a far cry from the more than tripling of homeschooling that the Census surveys estimated in Florida.

Numbers trickling out of other states, such as the 48 percent increase reported in Virginia, tell a similar story.

The rise in self-reported homeschooling likely reflects these increases in homeschooling, strictly defined, combined with other trends—like the increase in the number of students who left their school districts for established, full-time online schools—that may feel like homeschooling to participating families but don’t meet the legal definition.

This is a trend we observed before the pandemic, which the disruptions of COVID-19 accelerated: the lines between schooling and homeschooling are getting fuzzier.

New line-blurring options emerged during the pandemic. Students attending the Southern Nevada Urban Micro Academy last year were attending a school by most common-sense definitions of the term, but to participate in their municipally funded pandemic learning community, they had to legally register as homeschoolers.

All this line-blurring is happening for a reason. Before the pandemic, families wanted more power to shape their children’s learning environments than the public education system allowed. During the pandemic, more families were desperate for alternatives to what their local schools offered and created new options for themselves that revealed new possibilities.

It’s still not clear how many of these choices will prove fleeting, and how many families will quickly return to their pre-pandemic schooling arrangements. Still, making line-blurring options accessible to all families and sustaining them beyond the pandemic for those who want them will require new approaches to funding and regulating education that won’t be simple to enact. Understanding them will be essential if we want to build a public education system that is truly responsive to the needs of individual students.