Union militancy is rising in education beyond traditional teacher pay issues to address a broader “common good” agenda, but it seems that this progressive movement is struggling to keep its coalition united.

This new era began in 2018 when the Red For Ed movement sought dramatic pay increases in red states (Arizona, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and West Virginia) and intensified during the pandemic in blue states as unions fought to keep schools closed until effective Covid-19 vaccines became available. Post-pandemic, union activism (mostly in blue states) reflects teachers’ discontent with inflation reducing their real incomes and school environments becoming more difficult.

As always, teachers’ unions first priority is public spending on education. They want to greatly elevate teacher pay scales, which would require a significant increase in state and local funding. However, they seek more than just a larger share of the public education pie. In 2018, the Los Angeles teacher union sought to repeal Proposition 13, which held down property taxes and limited spending on schools. In Portland, Oregon and St. Paul, teachers voted to strike over salary increases that exceeded objective estimates of what the districts could afford. St.Paul teachers won a favorable agreement just days before their scheduled strike. Elsewhere, unions set up picket lines and closed schools, knowing that the districts’ nominal bargaining partners didn’t have the money to fund the settlements they were demanding. These measures weren’t irrational: unions are bargaining with local school boards, but their ultimate goal is to pressure the public and state legislators to fund public schools more generously. As the Los Angeles teacher union claimed in 2019, the schools are “broke by choice,” so there is no justification for respecting current overall spending levels.

To protect their core interests, unions continue to fight school closings. As enrollments decline, more districts must consider saving money by consolidating schools and disposing of some buildings entirely. This belt-tightening will lead to some unwelcome teacher reassignments and even layoffs, which unions will oppose. In Oakland, unions have won the right to bargain over school closings. This is a new provision; only time will tell what it means. The need to bargain with the union over school closings might force the district to seek other ways to cut spending, keeping under-enrolled schools open even during a district financial crisis.

Killing the competition from charter schools and vouchers is another familiar objective. Still, unions in California and Illinois hope they have new leverage to bargain for reduced caps on the number of charter schools allowed, effectively limiting charters’ access to vacant public school buildings and increasing regulation. They also hope to discourage any school board or state actions that would create escape routes from district-run schools for parents, bleed off money from districts, or create non-union employment for teachers. They want to make local politics permanently more friendly to teachers and groups they hope to lead in a powerful progressive coalition. They are also determined to run billionaire-led foundations out of public education, believing that these foundations sponsor charter schools and test-based accountability for teachers.

However, today’s militancy goes beyond wages and working conditions to embrace a broader “common good” agenda. Local teacher unions in many big cities (Oakland, Chicago, St. Paul, Portland), encouraged by the national NEA and AFT, are pushing for dramatic increases in social, mental, and physical health services for children in schools, plus policies friendly to immigrants, people without housing, and low-income and minority families. Union leaders want to drive home the idea that teachers aren’t accountable for student learning if their kids have unaddressed needs. Negotiators in Oakland, St. Paul, and Los Angeles want district and state support for “community school” models, which address everything from social services for families to nutritional, mental, and physical health support for students. The just-settled strike in Newton, MA was mostly about teacher pay and benefits, but the union also pressed demands for a social worker in every school.

Such demands support teachers burdened by student behavioral issues and low school attendance due to health and family issues. Making social services broadly available (not just in one or two demonstration schools where social and health service agencies pour all their resources) will require a significant reallocation of public and private resources and an overall increase in public and private spending on health and social services. To achieve these costly objectives, unions must persist for a long time, create immense leverage to change local city and county priorities, and cause citizens to ramp up their charitable giving.

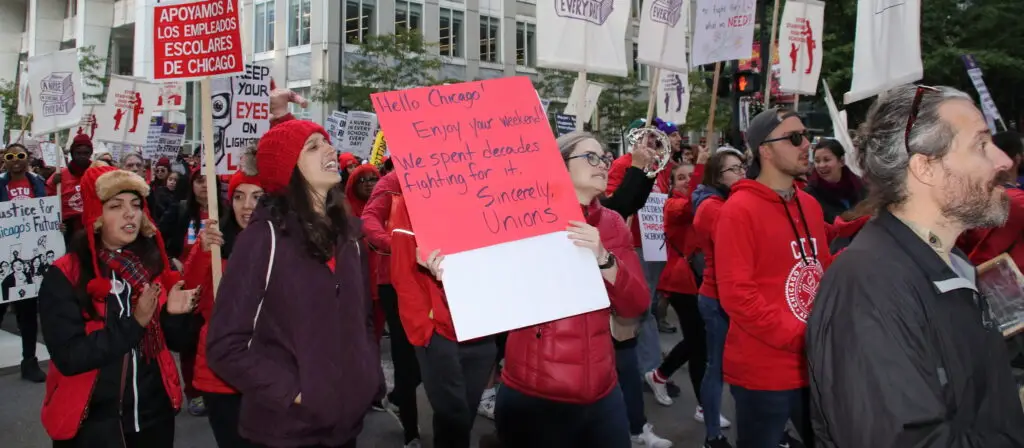

The unions pursue these objectives through deep organizing: constant messaging to their members and active engagement with other local labor, minority, and left-leaning organizations, as well as through more public-facing actions. These include demonstrations, unfair labor practice charges, strike threats, vigils at the homes of superintendents and school board members, and ultimately, picketing and school closures. Unions have used all these tactics before, but their goals and degrees of mobilization are much greater than before the pandemic.

Even more broadly, unions hope to make states and localities much more supportive of immigrant families and families experiencing homelessness, reduce police presence in schools and at demonstrations, and create better job opportunities for former felons, as an earlier Lens post documented. Union leaders can bring along teacher members who experience the problems that follow unhoused and immigrant children into the classroom. Some local teachers’ unions have also taken positions on the 2023-2024 Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which is far afield from schools but can create solidarity with other progressive groups.

As city school districts lose funding and cut employment due to ongoing enrollment declines, unions might have to return to a narrower focus on teacher pay and job security, at least for a while. But unions won’t give up on their broad social change agenda: they’ll just pursue elements of it selectively, depending on the urgency of teacher jobs issues and local receptivity. For example, the St. Paul union’s official bargaining agenda in early 2024 included all the above-named “common good” provisions. Still, the current strike threats focus on only one: social workers in schools.

It remains to be seen whether teacher unions can drive city and state policies and spending as dramatically as they hope. Making demands is one thing, but enforcing agreements where the other side needs more money and authority to comply fully is quite another. Districts might be unable to live within their budgets without closing some schools—even if the union has the contract-based right to bargain about it. Similarly, without funding, social service agencies can’t be forced to greatly increase their spending to provide services in dozens of schools, even if the local school board accepts contract terms calling for “community schools.” At some point, other members of the progressive coalition might have different priorities and withdraw their support, as Black-led parent organization The Oakland Reach did in 2023 when teachers shut down schools even after teacher pay and benefits issues were resolved.

What the unions can achieve after their goals have been written into collective bargaining agreements depends greatly on whether they can 1) credibly threaten to strike and 2) retain public support, especially from teachers who fear losing income and parents whose lives are disrupted when schools close. Recent strikes with “common good” agendas have generated pushback from parents, public officials, and newspapers. Some Oakland teachers returned to school during a strike rather than defy angry parents.

To progress on their broader agenda, teachers’ union leaders must play the long game, timing their demands and strike actions to align with public sentiments and budget realities. To date, unions have succeeded even at a time when the right has organized against them. Teacher unions can usually rely on support from public school parents and social welfare organizations and at least tacit acceptance from business interests and city governments. However, as we saw in Oakland, leaders of those other groups (including parents resenting strikes and progressives who might not want schools to take an increasing share of public and taxpayer resources) might unite in opposition. If union militancy generates new opposition, local union heads will be challenged to manage increasingly difficult local politics.

This piece was updated on March 6, 2024.