For those in the charter movement who have viewed chartering as a systemic reform strategy (not just an escape hatch for some kids), the prevalent theory of action for the last ten to fifteen years has been a “tipping point” strategy. The idea was to concentrate growth in targeted cities until districts either responded to competition or were entirely replaced by charters.

Looked good on paper. Sadly, though, things are not going as expected. Here’s why:

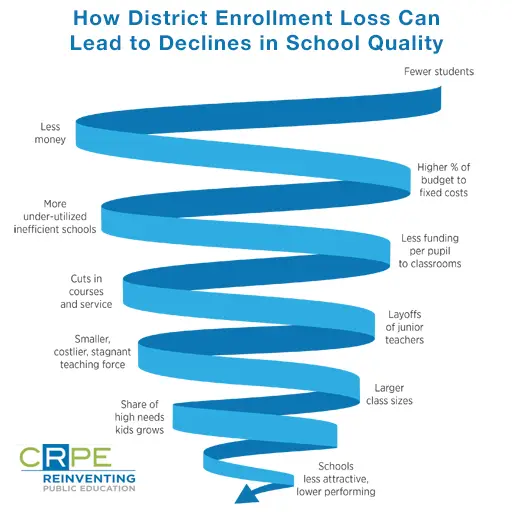

First, as charters hit significant market share, political opposition grows exponentially. School boards and superintendents are faced with a situation where they lose enrollment so quickly that the only thing they can do is close schools, lay off teachers according to seniority not quality (thanks to “last in, first out” requirements), increase class sizes, and slash their central office staffing and support levels. In some cities, districts also face an increasing concentration of the students hardest and most costly to educate, those with severe special needs, those who speak little to no English, those with the most severe behavior and mental health challenges and the least parental support. This combination of factors often triggers a slow death spiral that paralyzes politically bound superintendents and boards and ultimately harms students.

The Center on Reinventing Public Education has a new report out this week that makes clear that the financial challenges facing such districts arise from irresponsible labor contracts, failure to reduce semi-fixed costs in response to enrollment loss, and rigid and unsustainable pension and health care commitments. Still, as we say in the report, while this situation is not charters’ fault, it is in part their problem. In the eyes of the public, charter schools are causing harm to district kids. And any attempt to close under-performing or under-enrolled district schools means quick ousters for reform-oriented superintendents and board members.

Second, we’re seeing that in most cities, demand for charters slows significantly at around 40-–50 percent market share. About half of all families prefer district-run neighborhood schools for a variety of reasons.

Third, the supply of high-quality charters has not kept pace with the need, especially in tough labor markets and in Midwestern and rural states. In these areas, districts are sometimes better positioned—knowledge-wise, resource-wise, staff-wise—to provide high-quality and innovative public schools.

For all these reasons, and despite my own affection for the idea of all-charter systems, the charter community in most cities is failing to achieve the goals assumed by the tipping point strategy. If the typical urban district were a soda machine, it has been wobbling back and forth for several years and threatens to fall back on the reformers who are trying to push it over.

Consider the lessons from Oakland, a once reform “hot spot” but where charter growth has slowed to a trickle. When we talk to school providers there, they say they can still get charters authorized but the politics of district finance, combined with the saturation effect of having so many charter operators fighting over the same buildings, kids, and talent, are forcing them to look to other communities. Meanwhile, kids are paying the price for the district’s inaction.

So I’m not okay with the argument or attitude that reformers should either replace all of the traditional public schools with charter schools or just “let districts be districts” as Mike Petrilli recently argued.

I do not contend that districts need to turn all of their schools into charters in order to improve and compete. Some small, largely homogeneous districts can be very effective at centralizing and acting like big, successful CMOs, with a coherent, thoughtful approach to instruction, curriculum, and all the rest. But for large, dysfunctional urban districts with political boards and dismal performance, especially those now actively losing enrollment and facing the downward spiral described above, there is rarely a viable path for improvement and competition with charters that does not involve a partial or complete restructuring of what really is a failed delivery model.

In order to innovate, districts need to attract and retain entrepreneurial teachers and leaders. There is no amount of top-down directive that can inspire the zeal and commitment that it takes to serve the most challenging students. You can’t have high-performing, mission-driven schools without placing the locus of control and accountability at the school level. For these reasons, many districts should consider decentralizing all or part of their system, although this needs to be done strategically and only when schools can demonstrate that they have effective models.

That is the lesson we can learn from D.C. and New York City district reforms under the early years of Joel Klein’s reign. It’s possible to make centralization work under the right conditions, but not for the toughest schools and not in a sustainable way.

CRPE’s many years of work on the Portfolio Strategy make these arguments and more. We have also been developing tools and research-based resources to help the growing number of districts that want to move decision-making to the school level, a challenge that has serious implications for what tomorrow’s central office will look like and do. This month, David Osborne, whose seminal 1992 book, Reinventing Government, inspired our center’s founding, has released a new book that makes our case with stories and examples.

Some charter advocates cannot abide the idea of working with districts. Pessimistic that districts can be trusted to respect school-level autonomy, they prefer to keep charters outside the district sphere altogether. That’s a fine strategy if the goal is to help a limited number of students escape a failed system, but it doesn’t hold as an overall reform strategy. When districts create charter-like schools such as those underway in Indianapolis and Springfield, MA, the strategy can help a district right itself financially while still expanding the number of high quality schools.

We can argue all day about the right path forward for districts, but we ignore the problem at our peril. Figuring out how to help districts thrive in a high-choice environment is one of the toughest challenges out there. And figuring out what to do if they don’t thrive but still persist is even harder.

This blog was originally published on Fordham’s Flypaper.