This opinion piece was originally published on The 74.

“In a matter of weeks or months, artificial intelligence tools will be your kid’s tutor, your teacher’s assistant and your family’s homework helper.” -Robin Lake

In April 2022, I attended the ASU-GSV Summit, an ed tech conference in San Diego. I’d recently become an official Arizona State University employee, and as I was grabbing coffee, I saw my new boss, university President Michael Crow, speaking on a panel being broadcast on a big screen. At the end of the discussion, the moderator asked Crow what we’d be talking about at the 2030 summit. In his response, Crow referenced a science fiction book by Neil Stephenson, A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer. I was intrigued.

I’ve since read the book (which is weird but fascinating). The protagonist is a girl named Nell who is a pauper and victim of abuse in a dystopian world. By a stroke of luck, Nell comes to own a device that combines artificial intelligence and real human interaction to teach her all she needs to know to survive and develop a high level of intellectual capacity. The device adjusts the lessons to Nell’s moods and unique needs. Over time, she develops an exceptional vocabulary, critical physical skills (including self-defense) and a knowledge base on par with that of societal elites – which enables her to transcend the misery of her life.

Crow told the conference crowd last year: In 2030, we will have tools like this. In fact, he said, ASU and engineers elsewhere are developing them now. But if we reconvene in 2030 without figuring out how we get those kinds of tools to kids like Nell, we will have failed.

The recent and rapid advances in artificial intelligence have been on my radar for some time, but I came home from last week’s 2023 ASU-GSV conference even more certain that advances in artificial intelligence (AI) via models such as GPT-4 (the latest iteration of ChatGPT) and Bing will soon be used as radically personalized learning tools like Nell’s primer. That future seemed far off in 2022. But these tools are developing so fast, in a matter of weeks or months, they’re going to be your kid’s tutor, your teacher’s assistant, and your family’s homework helper.

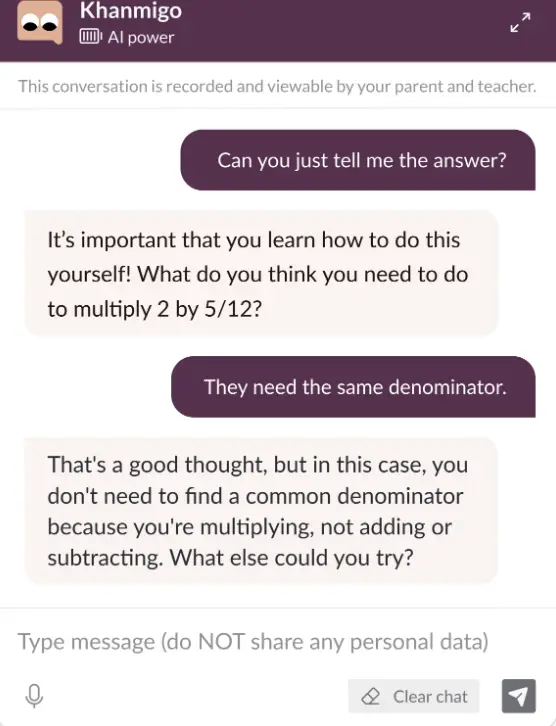

I attended several conference panels on AI, and one specifically on Khan Academy’s new tutoring program, Khanmigo, which is powered by GPT-4, blew me away. As Sal Khan said, he realized the power of this generation of AI: “This changes everything.” Of course, attendees discussed the safety and security risks and threats of using AI in the classroom. But what struck me was the potential for these sophisticated tools that harness the intelligence of the internet to radically personalize educational content and its delivery to each child. Educators can radically equalize education opportunities if they figure out how to ride this technological revolution effectively.

Khanmigo can do extraordinary tasks. For example, it writes with students, not for them. It gives sophisticated prompts to encourage students to think more deeply about what they’re reading or encountering, and to explain their thinking. It will soon be able to remember students’ individual histories and customize lessons and assessments to their needs and preferences. And that’s just the start. Khan described how one student reading The Great Gatsby conversed in real time with an AI version of Jay Gatsby himself to discuss the book’s imagery and symbolism. Khan said his own daughter invented a character for a story and then asked to speak to her own character — through Khanmigo — to further develop the plot.

Khanmigo — and likely other competing tools to come — also have the potential to revolutionize teaching. Right now, a teacher can use AI to develop a lesson plan, create an assessment customized to each student’s background or interests, and facilitate breakout sessions. This portends a massive shift in the teaching landscape for both K-12 and higher education — and likely even workforce training. By one account, the use of AI in colleges and universities is “beyond the point of no return.” A professor from Wharton School of Business at the conference said he actually requires his students to use AI to write their papers, but they must turn them in with a “use guide” that demonstrates how they utilized the tool and cited it appropriately. He warns students that AI will lie and that they are responsible for ensuring accuracy. The professor said he no longer accepts papers that are “less than good” because, with the aid of AI, standards are now higher for everyone.

‘A host of policy and research questions’

All this feels like science fiction becoming reality, but it is just the start. You have probably heard about how GPT-4 has made shocking advances compared to the previous generation of AI. Watch how it performs on the AP Bio or the bar exam. Watch how it performs nearly all duties of an executive assistant. Watch how it writes original and pretty good poetry or essays. Kids are indeed using this tool to write their final papers this year. But the pace of development is so rapid that one panelist predicted that in a year, AI will be making its own scientific discoveries — without direction from a human scientist. The implications for the types of jobs that will disappear and emerge because of these developments are difficult to predict, but rapid change and disruption will almost certainly be the new normal. This is just the beginning. Buckle your seat belts.

To be sure, the risks are real. Questions about student privacy, safety and security are serious. Preventing plagiarism, which is virtually undetectable with GPT-4, is on every teacher’s mind. Khan is currently working with school districts to set up guardrails and help students, teachers and parents navigate these very real concerns. But a common response — to shut down or forbid the use of AI in schools — is as shortsighted and fruitless as trying to stop an avalanche by building a snowbank. This technology is unstoppable. Educators and district, state and federal leaders need to start planning now for how to maximize the opportunities for students and families and educators while minimizing the risks.

A host of policy and research questions need to be explored: What kind of guardrails are available and which are most effective? Which tools and pedagogical approaches best accelerate learning? In what ways can AI support innovations that truly move the needle for teaching and learning? Education policy leaders, ed tech developers and researchers must begin to address these issues. Quickly.

I believe AI can make the teaching profession much more effective and sustainable. It can also put an end to the ridiculous notion that one teacher must be wholly responsible for addressing every student’s learning level and individual needs. AI — combined with novel staffing models like team teaching and specialized roles being piloted in districts like Mesa, Arizona, by my colleagues at ASU — could finally allow teachers to start working in subjects they’re most suited to. Instead of fretting about the lack of high-dosage, daily tutoring, which is the best way to address learning gaps, districts and families could see an army of AI tutors available for all students across the U.S. Parents who have been frustrated with the lack of attention to their children’s needs could set up an AI tutor at home.

But to go back to Michael Crow’s message: If technology and education leaders develop these tools but do not ensure they reach the students most in need, they will have failed. The field must begin to 1) track what is happening in schools and living rooms across the country around AI and learning; 2) build a policy infrastructure and research agenda to develop and enforce safeguards and move knowledge in real time; and 3) dream big about realizing a future of learning with the aid of AI.

As CRPE’s 25th anniversary essay series predicted in 2018, there are many things those planning for the future of education cannot know with the rise of AI: the effect of rapid climate change, natural disasters and migrations; shifting geopolitical forces; fast-rising inequalities; and racial injustices. It is clear, however, that education must change to adapt to these new realities. This must happen quickly and well if educators are to adeptly combine the positive forces of AI with powers that only the human mind possesses. To make this shift, schools will need help to transition to a more nimble and resilient system of learning pathways for students. CRPE has been writing about this transition for five years, and we are now launching a series of research studies, grant investments and convenings that bring together educators with technology developers to help navigate the path forward.

I hope that when people reconvene at ASU-GSV in 2030, AI will have been utilized so effectively to reimagine education that attendees can say they have radically customized learning for all kids like Nell. Despite the risks, using AI in classrooms could help eliminate poverty, reinvigorate the global economy, stem climate change and, potentially, help us humans co-exist more peacefully. The time is now to envision the future and begin taking steps to get there.