"Should families demand that schools take different approaches to supporting students' diverse needs?"

Schools and districts must look beyond their walls to support students

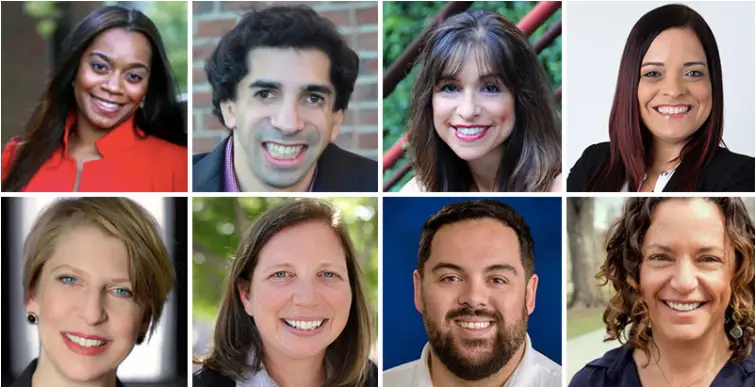

By Amy Berk Anderson

The short answer to the question is yes. Parents should demand new solutions for students with complex needs.

Yet, this is not a new reality.

Pre-COVID19, many families were frustrated because their children’s needs weren’t being met by their schools. What is different today is that many rules and regulations around the delivery of these services are now obsolete, making it nearly impossible for people to settle back into the same old routines. We must rethink roles and structures in order to balance continuity of learning with health and well-being.

Students are most likely going to be splitting time between schools and remote learning this fall. So, how might we reorganize our system to be more attentive to the needs of students and their families, and to use all our resources and assets to meet them?

Here’s one idea.

According to a recent USA Today poll, 20 percent of teachers say they are unlikely to go back to school in the fall. For those over 55, the percentages are higher. Let’s not lose these seasoned professionals. Let’s think about how to tap their talents and time differently — for example, as learner advocates, who could partner with families to navigate the complex and varied options involved in education and child development. Teachers who have an interest and skill set aligned with this role could meet virtually or in small groups with students and families to cultivate relationships and help them access resources aligned with their situations and goals.

What students need during non-classroom days may not be something a school can best provide remotely. Affluent families will pay for therapy, tutors, materials, and classes to supplement in-person learning. Families who are disproportionally impacted by COVID-19, whose children could benefit greatly from additional resources and advocacy support, can’t afford these opportunities.

In response, education systems and others could create funds that learner advocates and families could access. A group of organizations in Colorado, including RESCHOOL, has been testing this concept this summer. The response from families statewide, the majority of whom are people of color with household incomes below $50,000, has far exceeded the supply of funding.

We hope to raise more funds to continue during the school year, but this can’t fall on the backs of philanthropy alone. It is ultimately the responsibility of schools and districts to ensure continuity of learning, and this includes leveraging people and resources in fundamentally different ways than in the past.

Amy Berk Anderson is executive director of RESCHOOL Colorado. She was previously associate commissioner at the Colorado Department of Education, where she created and led the Division of Innovation, Choice, and Engagement.

Demanding that oppressive systems change isn’t enough

By Antonio Parés

Many families were already demanding something different. Now is the time for families to fight for something much better: wholesale change. Why? America’s schools, classrooms and resources are genuinely unequal and unfair, and many schools have caused irreparable harm to communities and generations of people.

We have all seen the video of a police officer, an agent of the state, killing a fellow American, George Floyd — yet another display of state-sanctioned racism and violence. It isn’t new or only found in policing. It exists in many of our country’s systems, including schools. How many children have had their life squeezed out of them by “school” as we know it?

Families should go much further than simply calling for schools to change. They shouldn’t go back at all — especially Black, Indigenous, LGTBQ and differently abled children’s families. Schools of all stripes don’t just miss the bar academically. They ridicule, oppress, arrest and hurt these children. It’s time for families to say, “Enough is enough.” Though COVID-19 and the corresponding school closures have been difficult, they have shown many that there are other ways to “do school.”

Families should band together in small groups, forming cooperatives, co-learning communities and microschools. They could share responsibility for the daily oversight of kids, pool their resources, leverage online content and bring educators into homes, neighborhood centers and churches. Community organizations, businesses and individuals could bring their assets to bear. Imagine small, safe, community-based spaces for children to engage in content with the support of caring adults and one another. Sounds better than what school could look like this fall and has looked like for decades for many families.

If just 5 percent of Denver’s Public Schools students didn’t return, the district would lose approximately $38 million. Not an insignificant sum, and when set against state cuts and impending decreases to other revenue streams that flow into schools, it is a powerful bargaining chip, to be sure.

What if these families see the benefits of “doing school” differently? What if they realize that demanding something different from systems that have done so much damage in the past won’t work? Maybe cooperatives and microschools are the kind of change they’ve long sought — self-actualization and liberation.

Families should abandon systems that have made it hard for so many to be, to breathe, and build a better future for their children and themselves in the process.

Antonio Parés is founder of Walnut Hill Workshop LLC, a firm specializing in helping new schools and nonprofits. He was previously a partner at the Donnell-Kay Foundation and led the development and startup of the Vela Education Fund.

We need a more sustainable approach to supporting families

By Jennifer Charlot

Families have gotten a special window into how learning happens for their children. They are no longer hearing about it secondhand. They are experiencing it themselves, reviewing packets, watching as teachers facilitate instruction, seeing in real time how administrative and policy decisions impact their lives.

Three themes surface as we listen to families.

Mental and emotional wellness: Health and safety concerns, fears about racial injustice and persistent social isolation from peers have made families sensitive to mental health challenges like anxiety and depression. It’s clear that for learning to happen, schools can’t just operate with business as usual, without giving children a space to process. One counselor for more than 300 students, or a five-minute morning meditation, feels insufficient to support children who are managing the challenges presented by society today. Families want to know that all teachers who engage with children are able to address, at minimum, their basic emotional needs.

Access to services: Distance learning made some families nervous about how their children with exceptional needs would get key services. Some districts asked families to waive rights to services because they were unclear how to provide them. The shutdown of buildings made it difficult to fulfill IEPs, especially for children who needed things like physical therapy or assistive devices. This highlights a need for better integration of resources between the classroom and the home. How can schools help to ensure that things children have at school are also present at home — sensory kits, physical therapy equipment, etc. — and that families are trained in using them?

One approach is for schools to consider more comprehensive strategies that might include partnerships with home care services or insurance companies so that the care children receive is not limited to what they can get when they are in school.

Families as partners: Many children with exceptional needs require a cocktail of services when they are in school. Students may have a speech therapist, an aide who follows them around during the day to ensure they are accessing learning, and a general education teacher. During distance learning, families are asked to play each of these roles, in addition to working and fulfilling other household responsibilities. This feels nearly impossible, especially given that they are not trained educators. However, with additional coaching, families can be better equipped to support their learners in the home.

Jennifer Charlot is a partner at Transcend, where she focuses on school design services and learning science. Transcend is a national nonprofit organization focused on supporting communities to create and spread extraordinary and equitable designs of school.

Schools can’t meet students’ needs with add-ons; everything has to fit together

By Julie Kennedy

Every school consists of hundreds of tiny, individual puzzle pieces — from big pieces, like what teachers are focusing on in their professional development, to small pieces, like how the teacher in Room 104 greets her students at the start of the day. In the best schools, someone (or some group) is holding the picture on the top of the puzzle box and every year figures out how to make sure all these individual puzzle pieces fit together meaningfully as part of a larger picture.

As we look ahead, families should focus on working with school leaders to expand and revise the picture on the top of the puzzle, to respond to a range of student needs that are even more clearly exposed during school closure. This will take more than just adding individual puzzle pieces. Far too often, urgent demands for change result in a series of reactions — adding a new SEL curriculum, a new tutoring program, new blended learning software — and piling these on top of an existing program. If we focus on the on-the-ground changes we want to see right away, we end up feeling like we’ve picked up pieces from a different puzzle and tried to fit them in. The pieces don’t fit, don’t stick and don’t add to a bigger picture.

What would it look like to focus on the puzzle box picture first? Some of the most incredible schools I’ve seen developed their program specifically to embrace the diverse needs of students. Some of these schools were founded with this DNA, and some have reimagined their program to ensure there is deep alignment between new ideas and practices and the rest of the core program.

One thing they share is that this work — serving students’ diverse needs — is incorporated into everything they do: how they train and support teachers, their daily schedule, their curriculum choices, their approach to family engagement and so much more.

Let’s start with challenging and supporting leaders to imagine how different their puzzle top picture could look, and then provide them with the resources and time they need to reconfigure and add in the missing puzzle pieces they need to put it all together.

Julie Kennedy leads the academic and character practice on the Impact Team at the Charter School Growth Fund. She began her career as a middle school science teacher in Newark and Boston.

Parents and educators can demand that schools make the most of their newfound flexibility

By Karla Phillips-Krivickas

The pandemic-related shutdown of our schools has confirmed that they were not designed to support the diverse needs of learners and are not very malleable. The very existence of special and gifted education programs acknowledges this and attempts to right this wrong for students thought to be outliers.

But teachers and parents have always known that the existence of the “average student” is a myth.

What parents observed during the school closures will increase pressure for more extensive and personalized supports. COVID-19 has thrown the diversity of student needs into sharp relief, but the push from parents to ensure that the needs of their students are met is not new.

It has been clearly seen through the evolution and growth of school choice. Beginning with parents seeking houses in “good districts,” from homeschooling to vouchers to online schools, the education landscape has changed dramatically in the past 30 years. Families have been emboldened to demand more and seek better.

The surge in interest in personalized learning demonstrates not only that parents are seeking approaches that are more tailored to the needs of individual students, but also that educators know they are needed.

Prior to the pandemic, efforts to break out of the traditional, standardized mold have been hindered by state and local policy obstacles and bureaucracies.

The way instruction is defined, seat-time rules, attendance requirements and even local traditions like bell schedules have stood in the way of innovation.

I have spent the past six years advocating for flexibility, but I never imagined that many of the most burdensome policies would disappear overnight. States quickly extended flexibility to schools and districts to allow them to quickly implement remote learning efforts during the pandemic. The question that still needs to be answered is whether schools will take advantage of this flexibility to develop systems that better meet the needs of their students.

Great educators and leaders are out there, but they need policymakers at every level — federal, state and local — to partner with them and be bold. They need policymakers who want to move past crisis management and temporary solutions like waivers.

Parents can help enact long-term, sustainable solutions to meet every child’s needs, including their own, by advocating not only to their school leaders but also to policymakers, including school board members and state legislators.

Karla Phillips-Krivickas is senior director of policy at KnowledgeWorks. She previously served as policy director for the Foundation for Excellence in Education and has also served as special assistant to the deputy superintendent at the Arizona Department of Education, as the governor’s education policy adviser and as vice chair of the Developmental Disabilities Planning Council.

Schools must seize this opportunity to rethink how they educate all learners

By Lindsay Jones

Before 1971, it was illegal in several states for students with disabilities to attend public schools. Families, and dedicated educators, changed that. They brought anti-discrimination lawsuits against states and advocated before Congress to create a system that included and valued their children.

For the past 40 years, that system has included students with disabilities, but it hasn’t always valued them.

We saw this most clearly in March, when schools closed due to COVID-19, and several respected districts and educators immediately claimed they couldn’t possibly educate students with disabilities remotely. Within two weeks, there were proposals in Congress to completely eliminate the civil rights of students with disabilities for at least one year. Most recently, major education organizations have put forward proposals to weaken civil rights protections for students based on their belief that they can’t educate students with disabilities remotely. As an advocate for children with disabilities, and as a parent, it makes me sad and angry to see some in our community abandon our children so quickly.

But we have also seen incredible innovation from amazing educators who are creative and dedicated. My organization, the National Center for Learning Disabilities, joined with more than 40 others to start the Educating All Learners Alliance that highlights the amazing work schools across the country are doing to support students with disabilities. Much of what we are learning must continue.

Now is the perfect time to reimagine how schools support all students, because school won’t look the same for any student when they return in the fall.

Imagine if districts took this opportunity to design their new school year based on what they know about how to teach the most complex learners. Research demonstrates that if we design schools with complex learners in mind, all students benefit. When teachers are trained to educate students with reading disabilities, they are better teachers for all kids learning to read. When systems individualize content for students with disabilities in the general education classroom, they do a better job customizing for all student learning.

Students with disabilities will still need specialized instruction and supports that others don’t, but when districts include and value them, they value all students more.

For years, we’ve talked about ending the factory model of education, and now we actually have that opportunity. If, after all this upheaval, things just go back to normal, with one teacher, in one room, using one book for all 40 kids, we’ll all have failed. Families and dedicated educators can’t allow that to happen.

It’s time again to stand up for change.

Lindsay E. Jones is president and CEO of the National Center for Learning Disabilities.

Schools must prepare to support students socially and emotionally

By Sam Drazin

The 2020-21 school year promises to be unlike any other. Families are looking to schools for guidance in how we pick up the pieces of missed instruction, missed support services, missed social opportunities and missed celebrations. They will rightfully demand that schools be prepared to address the needs of all students not only academically but also socially and emotionally.

As such, schools must take a different approach than they have in the past to supporting students’ diverse needs. A proactive approach to social-emotional learning, or SEL, is a clear pathway to achieving this goal. But schools must think beyond a canned SEL curriculum because the challenges — and the stakes — are higher than ever.

Families can help ensure that this critical work occurs by advocating for schools to implement high-quality SEL programming that ensures accessibility of materials to all students and provides parents with education and resources to become partners in these efforts. They can help ensure that schools consider the best ways to seamlessly integrate social-emotional learning into the core academic subjects. Too often, schools teach SEL in isolation from subjects like English, math, history and science. Instead, they should be considering how best to teach social-emotional learning in conjunction with them.

In many states, students will have been out of classrooms for nearly six months. When school begins again, virtually or in person, students will not return as they left. And herein lies the challenge for educators: How do we address the needs of all students when the spectrum of individual and collective trauma is so broad? Troublesome achievement gaps have widened. Students have missed out on vital services and interventions. Kids have been cut off from their peers. Families are struggling with new landscapes of their own. Our nation is grappling with deep, difficult questions about equality and justice.

Students’ traumatic experiences are varied and will inevitably need to be processed, reflected on and supported by teachers and school personnel. Before schools can address academic regression, they need to first address students’ social-emotional well-being.

To construct and deliver high-quality SEL programming, education leaders will need to use the summer months to plan and collect resources. They must train their educators on how best to deliver materials, virtually and in person, to be most effective in supporting all students.

Families’ advocacy for schools to support their students socially and emotionally through the uncertainty they face this fall will offer schools opportunities to strengthen connections and extend SEL into homes.

By planning for the year ahead, and taking advantage of the opportunities this current situation affords, schools can support their students emotionally through this crisis and lay a foundation to support them more effectively in the future.

Sam Drazin is founder and executive director of Changing Perspectives, an organization that provides schools with disability awareness programming designed to help build empathy. He is also a former elementary school educator.

Schools must treat parents as full partners

By Bárbara Rivera Batista

Education is a human right. Students and families — regardless of their economic, social and educational circumstances — should feel safe at school to ask questions, bring concerns and seek real solutions. They should feel they can work together to help schools meet the needs of each student and family.

The integration of parents is important. Bringing them to the table helps schools understand the circumstances and realities of each family.

Fostering relationships with all students and families is crucial to support students with special education, social-emotional or other needs. These students and families need to understand that they have an ally or an advocate within the school who can understand and empathize with the challenges of this period of remote learning, and that school staff have their child’s best interests at heart and will seek solutions.

As a small school with staff dedicated to fostering and supporting these family relationships, Vimenti is well positioned to provide targeted outreach and guidance to address each student’s unique needs and challenges. All schools should strive to dedicate time and resources to improving the strategies for family communication and support, making more purposeful connections, understanding needs and challenges, and crafting solutions for common and individual areas of need.

The integration of support staff to distance learning is also important. Staff such as psychologists, nurses and therapists and special education teachers are necessary to meet particular needs students and families have.

Giving students and families support resources and responding to individual needs allows schools to create a sustainable learning process for each student and family.

Bárbara Rivera Batista is director of Vimenti School, an initiative of the Boys and Girls Clubs of Puerto Rico and the first public charter school on the island.