Note from the authors: We share our most recent COVID-19 findings during a critical moment, as the recurring impact of systemic violence against Black people devastates our communities and the nation. As we work to inform efforts to build a more equitable education system, we must acknowledge the pain wrought by these injustices.

After three months of school closures, America’s school districts face the unprecedented and unknown reality of student learning loss. What are school systems doing this summer to confront inequities exacerbated by school closures and prioritize students in greatest need of academic, social and emotional support? How are they using this time to prevent those inequities from continuing this fall?

Summer offers an opportunity for districts to begin addressing learning gaps that emerged this spring, as well as other needs—like social interaction and special education services—that were unmet while school buildings were closed.

Our latest analysis shows far too few districts are capitalizing on this opportunity. We are launching a new database analyzing summer learning and fall reopening plans in 100 school districts and 18 charter management organizations (CMOs) across the country, serving over 9 million students and representing all 50 states plus the District of Columbia.

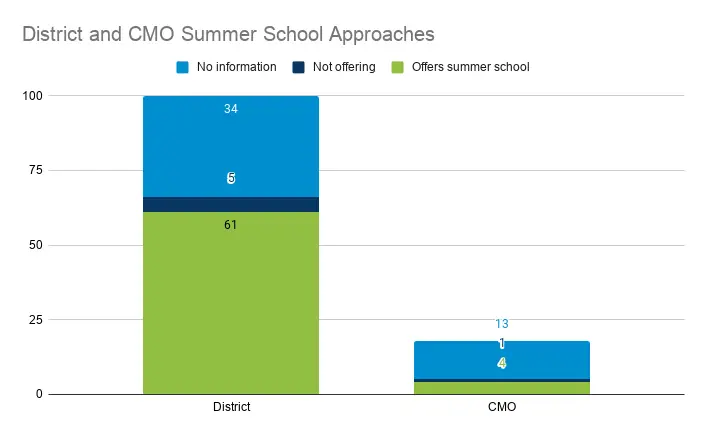

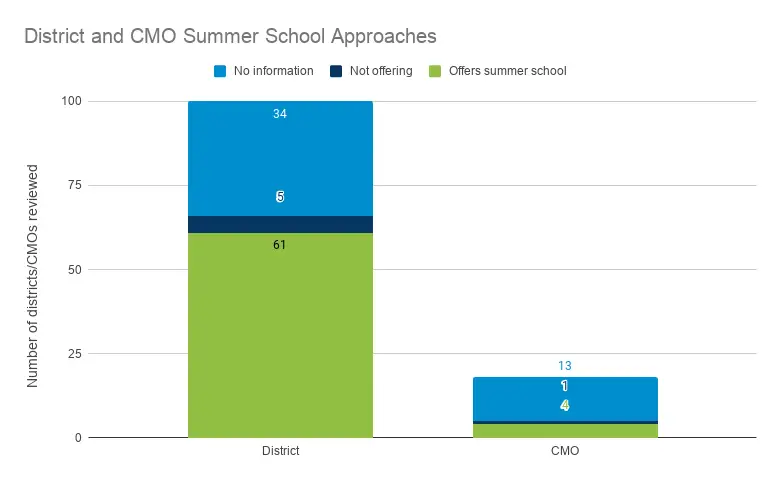

61 of 100 Reviewed Districts and 4 of 18 Reviewed CMOs Communicate They Are Providing Summer School

Less than half (47 of 100) of the districts in our review offer summer school to elementary or middle school students, and 58 of 100 districts offer summer school to high schoolers.

Only four of the eighteen CMOs we reviewed (22 percent) plan to provide summer school for elementary or middle school students and five (28 percent) for high school students.

Most of the remaining districts and CMOs we reviewed—34 of 100, or 34 percent, and 13 of 18, or 72 percent, respectively—haven’t yet announced their plans for summer school on their website or social media channels.

Our spring analysis found that even in districts that offered instruction, students received far less support than they normally would. For example, elementary school students often received just 30 to 90 minutes of instruction per day, and these efforts relied heavily on parents.

Many students received just a sliver of typical instruction this spring, and are not likely to receive make-up support over the summer.

Many of these schools and districts are hard at work planning behind the scenes with state agencies, labor unions, and community partners to untangle the complex logistical challenges the return to school this fall poses.

This summer presents a perfect time for districts to pilot new strategies not usually in their repertoire, and instead try to rebuild something different. Freed from the time constraints of the school year, and given the flexibility to focus learning efforts on students most in need of support, summer gives schools space to try new approaches to remote instruction, from online interventions for small groups to summer academies and enrichment programs. Unfortunately, many districts do not appear to be making the most of the flexibility summer affords.

Districts Take a Traditional Approach to Restoring Missed Content or Skills from This Spring

The districts and CMOs that will offer summer school this year tend to provide programs similar to years past. Most of these districts (68 percent, or 32 of 47 offering summer school) focus efforts on reviewing content needed to meet course- and grade-level standards for elementary and middle school students. For high school students, 83 percent of districts (48 of 58 offering summer school) provide programs focused on credit recovery.

The most pervasive difference seems to be format: 66 percent (31 of 47) of the districts that provide summer school are doing so virtually for elementary and middle school students, and 74 percent (43 of 58) for high school students. A few districts are providing blended virtual/in-person approaches. DeKalb County School District tentatively plans to offer its students eight days of in-person instruction and two days of virtual instruction, and Bismarck School District 1 may provide in-person small-group instruction in addition to its summer virtual learning platform. San Diego Unified School District plans to provide in-person programming for high school students.

Another portion of districts—17 percent, or 8 of 47, providing elementary/middle summer programs and 9 percent, or 5 of 58, providing high school programs—offer varied formats based on subject or grade level. In Wichita Public Schools, K-8 students identified as needing intervention will be mailed home a “summer suitcase” with hands-on learning materials in reading/social studies and math/science, supplemented with online skill development programming. High school students, on the other hand, have access to virtual-only credit recovery and acceleration courses.

About half of districts we reviewed provide enrichment options to elementary and middle school students (51 percent, or 24 of 47) and high school students (47 percent, or 27 of 58). El Paso Independent School District offers weeklong online classes in topics such as fine arts, technology, health and wellness, college and career readiness, and languages. Los Angeles Unified is working with a variety of industry partners across the city to provide “integrated theme units” for all grade levels on topics like sports medicine, environmental science, and coding.

Just 17 districts we reviewed offer coordinated programs through other organizations in their communities. In addition to district-led virtual personalized learning programs on theme topics, Kansas City Public Schools has partnered with the local Boys and Girls Club to provide in-person summer academic and enrichment programming. Oakland Unified School District offers a hybrid program at certain schools, with academic intervention in the mornings taught by certificated district teachers and enrichment activities in the afternoon led by community agencies.

None of the districts we reviewed mentioned summer training programs for teachers or staff, and we have yet to see any information posted explaining whether teachers of record will be staffing summer school courses or given the opportunity to practice new virtual strategies in preparation for fall.

Districts Prioritize Credit Recovery and Course Review for Struggling Students

Our spring analysis found that two months into closure, about two-thirds of the districts we reviewed provided comprehensive remote learning plans with formal curriculum, instruction, and progress monitoring. Only a third of districts tracked student attendance, and half graded student work. The districts that tracked which students were able to connect to remote learning, and how they fared academically, are now best prepared to identify “missing” students or students most in need of summer interventions.

Among districts providing summer school, 45 percent (21 out of 47) assign elementary/middle school students to summer programs, and 40 percent (23 out of 58) assign high school students. These are usually credit recovery or review courses.

Districts who refer students are most likely to do so based on grades or a combination of criteria that can include grades, attendance, and special population status. For example, Broward County plans a reading academy for third-grade students who did not meet literacy standards, and may have been held back in third grade during a typical school year under Florida’s automatic retention law.

Henry County in Georgia offers a referral-based but voluntary K–8 summer school program. Teachers create summer personalized learning plans for students in danger of not being promoted to the next grade. Summer school teachers will then use that plan to support each student’s learning.

A higher percentage of districts also allow students to opt into summer programs: 55 percent (26 of 47) for elementary/middle school students and 64 percent (37 out of 58) for high school students.

Fresno Unified School District in California takes an “opt out” approach to its Summer Academy, referring specific students to its reading and math intervention, bridging, and credit recovery classes based on grades, credits, and learning loss identified in the fourth quarter. The district takes an “opt in” approach to its Summer Camp, opening up remote learning camps in STEAM and career development to any interested students. It also provides an extended school year specifically for its students with special needs.

More Questions Than Answers on Summer School Accessibility for All

Given that summer learning is understandably almost entirely virtual, students will need access to technology and the internet to attend summer school. Districts’ communication on technology distribution for their summer programs is largely silent. It may be that districts assume students will continue to use devices or wifi, or they will redistribute technology and hotspots to priority students referred for summer school. It may help explain why so few districts were able to offer ambitious summer learning plans. This much is clear: the connectivity challenges that hampered remote learning this spring are unlikely to have vanished.

While we believe summer remains a missed opportunity, our analysis in the coming weeks will examine whether districts are seizing this opportunity to overcome the dizzying logistical challenges that accompany the return to school this fall.