Last spring, fewer than half of the nation’s school districts expected teachers to deliver remote instruction, grade student work, and take attendance. Districts’ inaction appeared to be closely linked to states’ unclear expectations.

As the pandemic spreads, districts across the country have announced they will open remotely, in some cases only weeks away from the first day of school. But our analysis of state reopening plans suggests too many states are not setting standards for what remote learning should look like. While states are not waiving instructional requirements outright, they are not being clear about how schools should grade students’ work, monitor attendance, or assess graduation requirements. These trends, if continued, could reproduce last spring’s remote learning challenges, where many schools lost contact with students and students anxiously waited for clarity about whether they would graduate on time.

But it’s not too late for states to set clearer standards to ensure remote learning will work better this year. Leading states are establishing clear requirements for learning, raising the bar of what is expected, and providing additional support to help local districts meet these requirements. For example:

- New Mexico is the only state that requires districts to add days to their calendar to make up for lost instructional time, and provides new funding to support the shift.

- Oklahoma allows districts to use Saturday as an instructional day to give them flexibility to adjust their calendars and still ensure students receive the state-mandated 1,080 hours of teaching over the course of the school year.

- In Texas, districts that offer remote learning must record live, teacher-led instruction in the same way they would during in-person instruction. For districts to receive funding, they must gain state approval for how they will track attendance when students in remote settings are learning through independent work or watching pre-recorded lessons.

- Kansas recommends districts adopt a competency-based grading system and backs up that recommendation with detailed competencies for all grades and subjects, as well as recommendations for how to implement such a system.

- Virginia provides the most detail of any state about changes to graduation policy for the 2021 class. For example, the state allows districts to drop a first-aid requirement, and confirms that physical education is still required but the minutes have been waived.

More states are acting to ensure schools deliver a minimum amount of instruction this year, but what that means in remote settings remains ambiguous.

In a typical year, states require schools to deliver a minimum amount of instruction per year, often calculated by hours and days. As schools around the country closed their doors last spring, many states waived instructional time requirements to give schools and families the flexibility to adjust to a global pandemic people knew little about. The predictable result: students received far less instruction than they would have under normal school conditions.

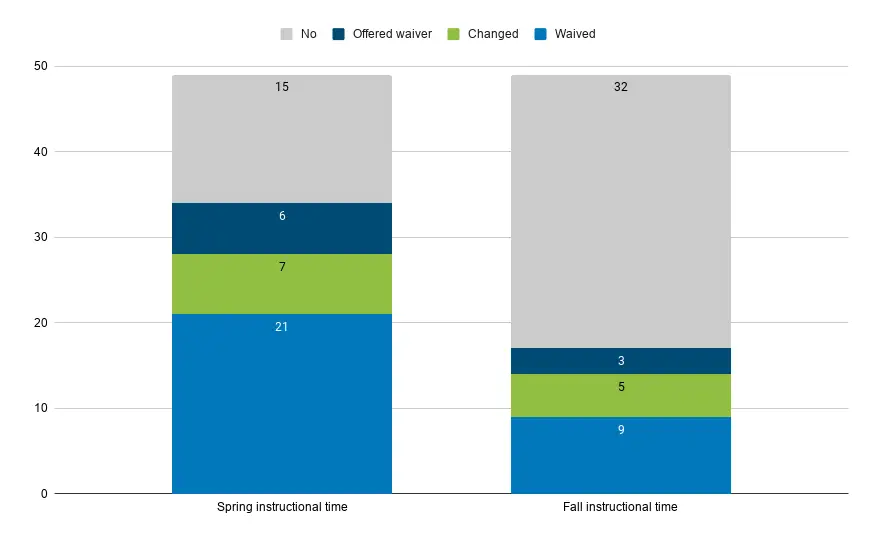

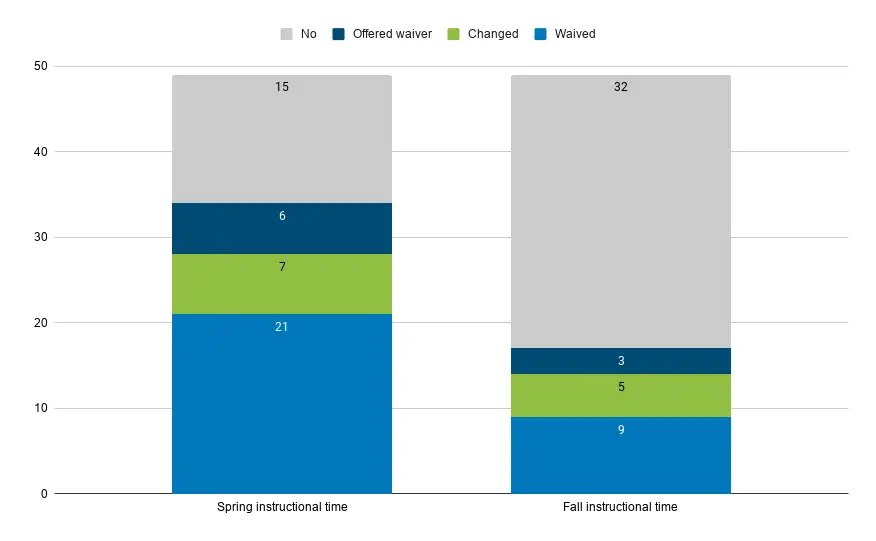

Our review of fall reopening guidance suggests few states are repeating actions from the spring. Ten states have waived instructional time requirements for the 2020-21 school year, in contrast to last spring, when twenty-one did so.

Two-thirds of states have not announced any changes to instructional minutes for the 2020-21 school year

Sources: Spring data from the Institute for Public Policy Research. Fall data from CRPE’s State Response Database.

Note: “No” means no information or no change in state policy.

While the majority of states are retaining their authority over instructional time, only five states set clear expectations for what counts as instructional time in remote settings. One of them, California, passed a bill that revised how instructional minutes are calculated. School districts are required to certify the “time value” of assignments to ensure students have sufficient access to instruction in remote settings. Actions like California’s can help ensure that students gain sufficient access to instruction in remote settings.

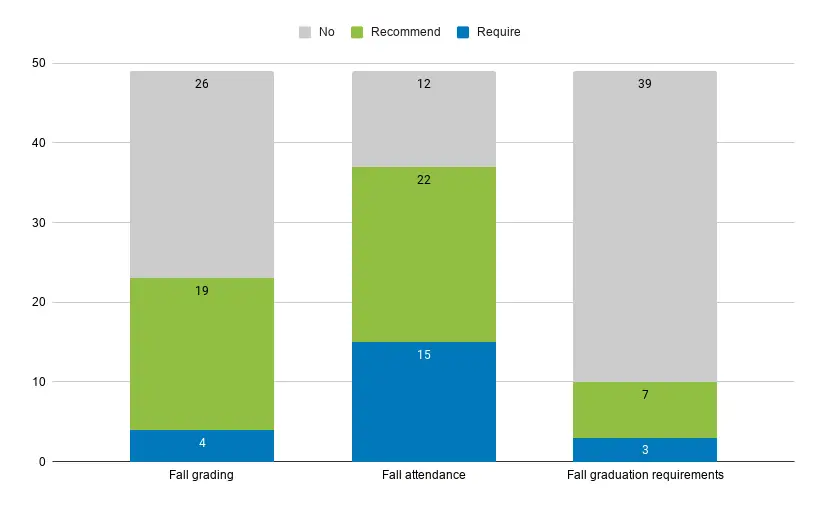

States aren’t setting clear expectations for tracking attendance, grading, and graduation.

The vast majority of states are not setting new requirements for attendance-taking, grading, or graduation—instead leaving it up to districts to adjust local policies to accommodate remote learning. If states do not address instructional policies now, we are likely to see the kind of variation in quality we observed in the spring: when districts were left to their own devices, some schools expected students to show up daily to learn and closely monitored their progress toward academic benchmarks, while other districts did not.

States leave instructional requirements up to districts

Source: CRPE’s State Response Database.

Note: “No” means no information or no change in state policy.

Attendance-taking was a blind spot for many districts last spring. Fewer than a third expected schools to track student engagement. This fall, nearly every state is requiring districts to take attendance, but they are not helping districts navigate the complexities of doing this in a virtual setting. Only a handful of states waived attendance requirements this year—Maine, Missouri, and North Dakota. But the majority of states are missing an opportunity to guide local decision-making.

Just 10 states set new requirements to facilitate attendance-taking in remote settings. For example, Mississippi created new reporting requirements so districts can only mark a student as present when the student logs into an online learning system or makes one-on-one contact with the teacher. Illinois requires that districts maintain daily contact with students and their families, whether learning is in-person or remote.

Grading helps teachers, schools, and families monitor student progress toward academic benchmarks. This fall, however, states are staying silent on the issue—half of them provide no information or guidance. Those that do offer recommendations are still expecting districts to figure out what a grading policy should look like in remote and hybrid settings. For example, a quarter of states recommend that districts consider mastery-based grading because it offers flexibility for remote learning. But competency-based instruction is difficult to implement in the best of times; doing so during a pandemic without major new investments may be foolhardy.

States are most silent when it comes to graduation policies. Communicating changes now means that high schools can plan schedules and allocate teachers efficiently—and students can begin planning postsecondary transitions. The risk is that inattention now could lead to waivers or last-minute changes later, like we saw in the spring when 90 percent of all states waived graduation requirements.

Thirty-nine states either provide no information or tell districts it is their responsibility to come up with a plan. A handful of states have recommended that districts take remote learning into account when assessing their graduation policies. Oregon, for example, reminded districts that there are various ways for students to earn credit for learning, and to make use of those flexibilities this year. Only three states communicated to districts that graduation requirements will be changing for the 2021 class: Massachusetts, Ohio, and Virginia.

*

A more productive state role is possible, but the window to address the gaps in remote learning we saw last spring is rapidly closing. States must act now to ensure students have access to quality instruction, whether they are learning at home or at school.