This piece was originally published by The 74.

New national test scores again show that students have critical gaps in skills and knowledge as a result of pandemic-induced school disruptions. The dip in reading and math achievement on the National Assessment of Educational Progress speaks to the continued need for instruction that exposes students to engaging, grade-level content combined with targeted help for those who missed certain skills. This learning acceleration strategy can be more effective than remediation, in which students work their way through material below their grade level to address learning gaps.

Last fall, the Center on Reinventing Public Education found that almost all of America’s 100 large and urban districts planned to prioritize at least one learning acceleration strategy, but only 20% intended to offer a comprehensive suite of approaches to help students catch up.

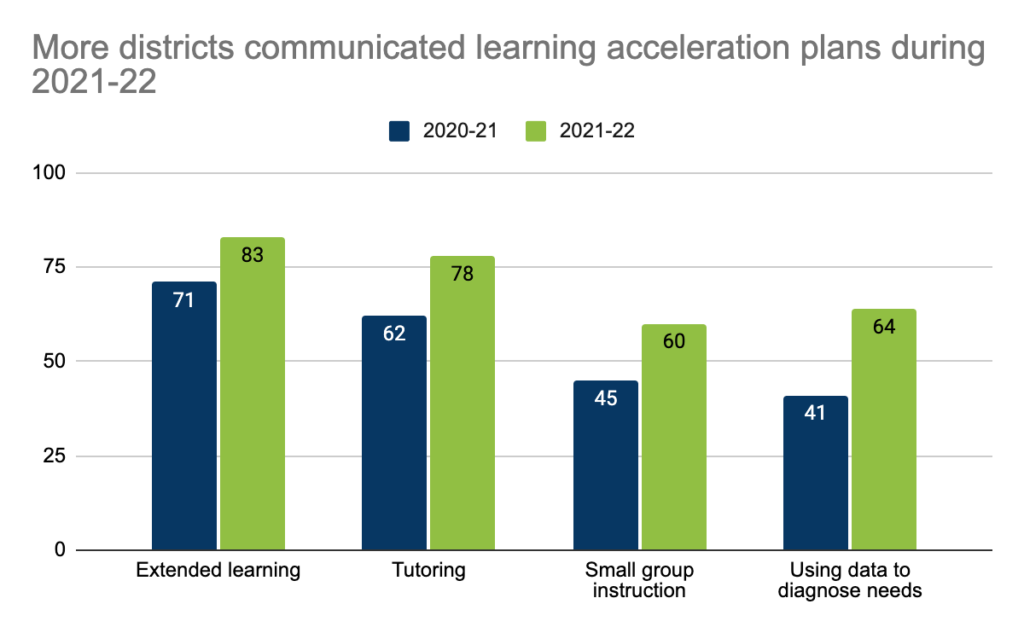

Our new review of spending plans reveals about 1 in 3 large U.S. districts (34) plan to incorporate all four evidence-based learning acceleration strategies — tutoring supports, extended learning opportunities, small-group instruction and use of data — a sign that more students may be poised to receive such help.

We do not know how successfully districts are implementing these plans, however. While most districts signaled that they’re also assessing students’ academic progress and/or their emotional needs, only a fraction publicized the results, according to our review. It’s also unclear how or whether districts plan to measure the effectiveness of the strategies to address learning loss that they plan to carry out.

The majority of districts plan for some form of learning acceleration, primarily through extended learning and tutoring

This latest analysis comes from our larger review of districts’ federally mandated spending plans for their COVID relief money. We also reviewed data from other public sources, including districts’ proposed annual budgets and recovery strategies they reported for 2021-22. Districts may continue these efforts through 2024, the deadline to spend the federal funds.

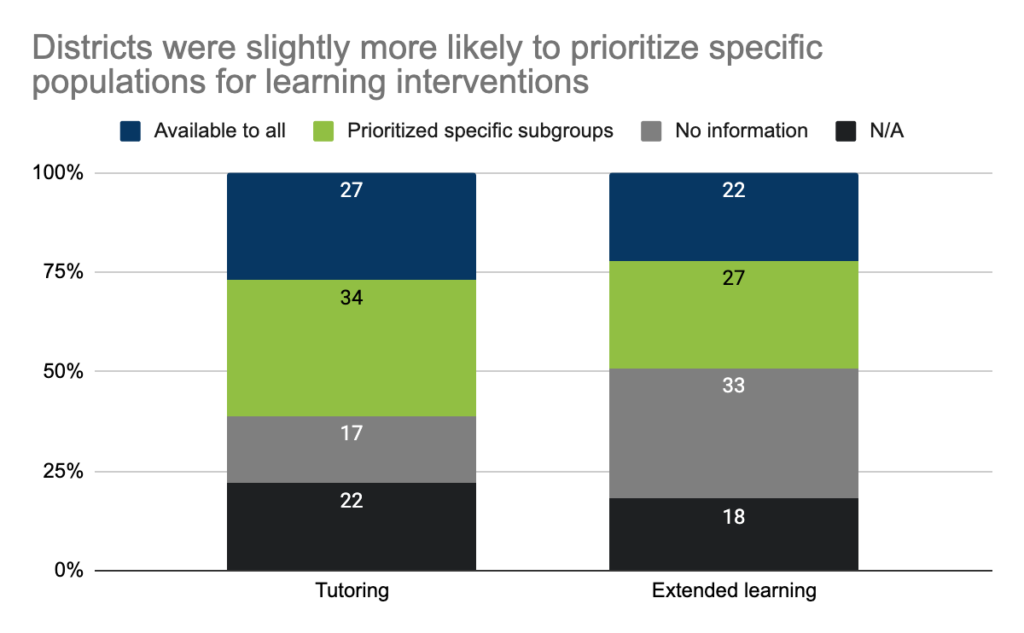

Nearly 8 in 10 large and urban school districts (78) said they planned to offer tutoring during 2021-22 — 16 more than the year before. Of these, 27 offered tutoring to all students and 35 targeted specific subgroups. Guilford County Schools in North Carolina, for example, used an algorithm to identify students in most need of tutoring. Other districts, like Red Clay Consolidated in Delaware, described populations they would prioritize, such as newcomers, long-term English learners, migratory students and children with disabilities.

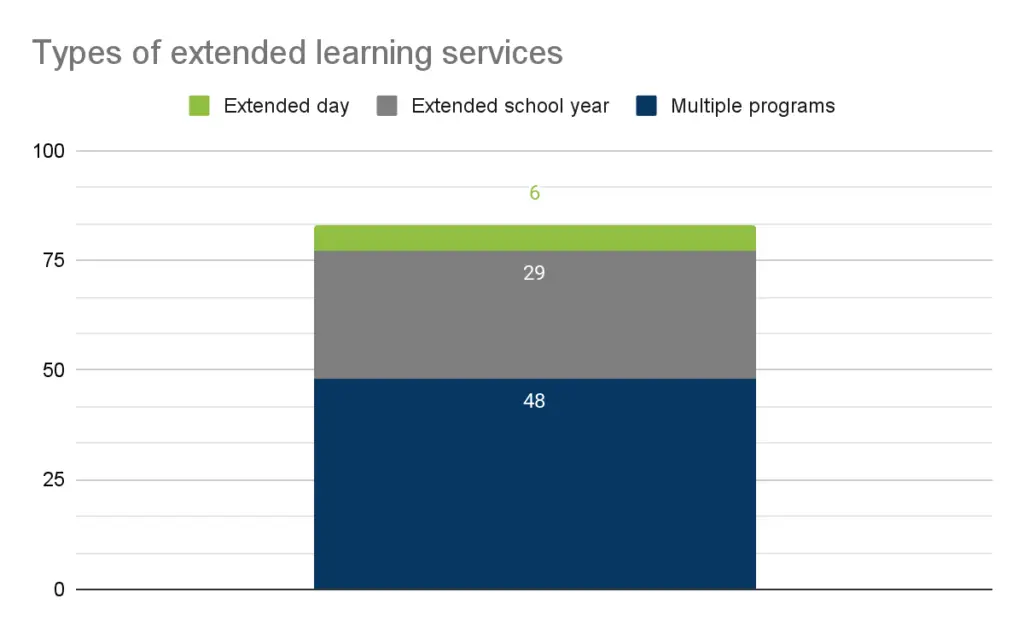

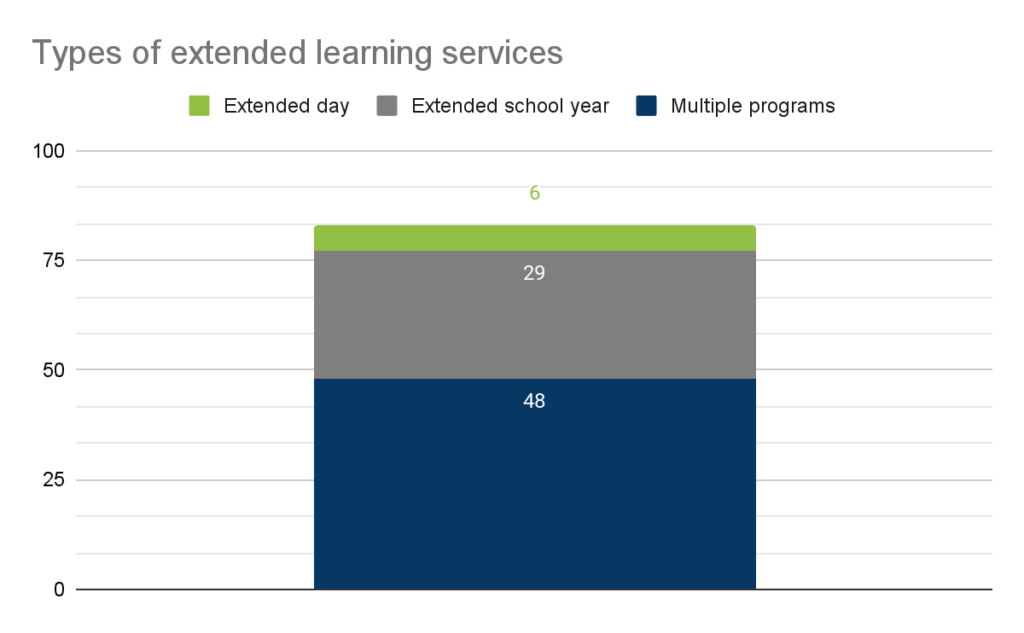

A slightly larger share of districts (83) shared plans for extended school services, including lengthening the school day (6) or offering summer programs (29). But most districts (48) opted to offer a combination of extended learning opportunities.

Roughly one-fifth of districts (22) offered these learning services to all students, but slightly more (27) prioritized tutoring for subgroups, such as elementary students and English learners.

About 1 in 3 large U.S. districts said they’d offer small-group instruction (60) or use data to diagnose student needs (64).

The number of districts that signaled they’d employ all four learning acceleration strategies increased overall. During our initial review, just over one-fifth incorporated every acceleration strategy in their recovery plans. The latest review shows about 1 in 3 large districts (34) intend to do this now.

While most districts had a plan to assess student progress in fall 2021, few provided details on how this data would be used moving forward

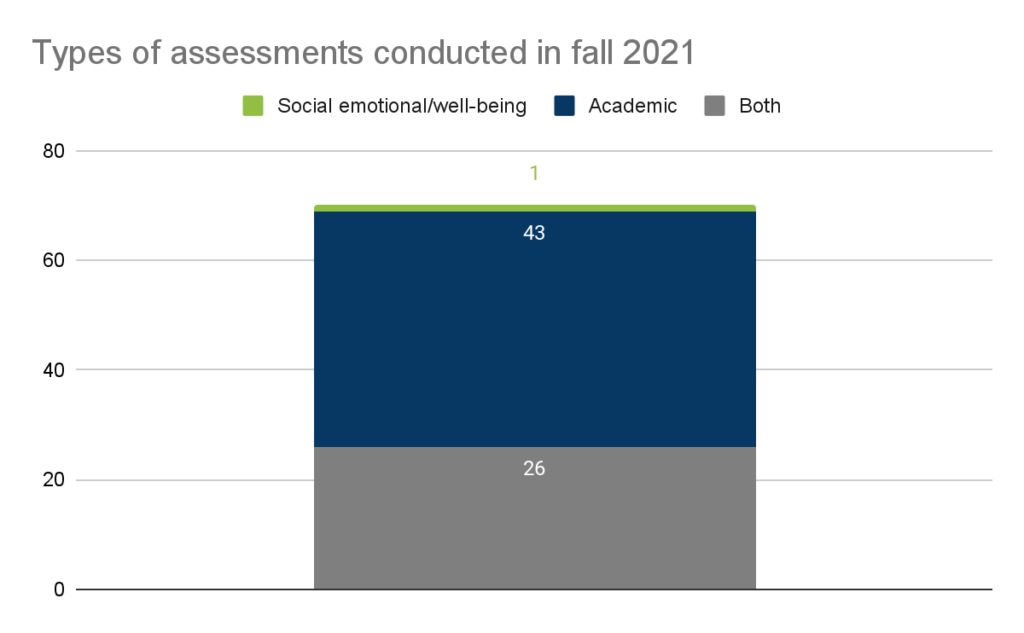

According to our analysis, 70 districts shared evidence of assessing students’ academic or social needs in fall 2021. Of these, most prioritized academic assessments, but a handful also gauged students’ well-being.

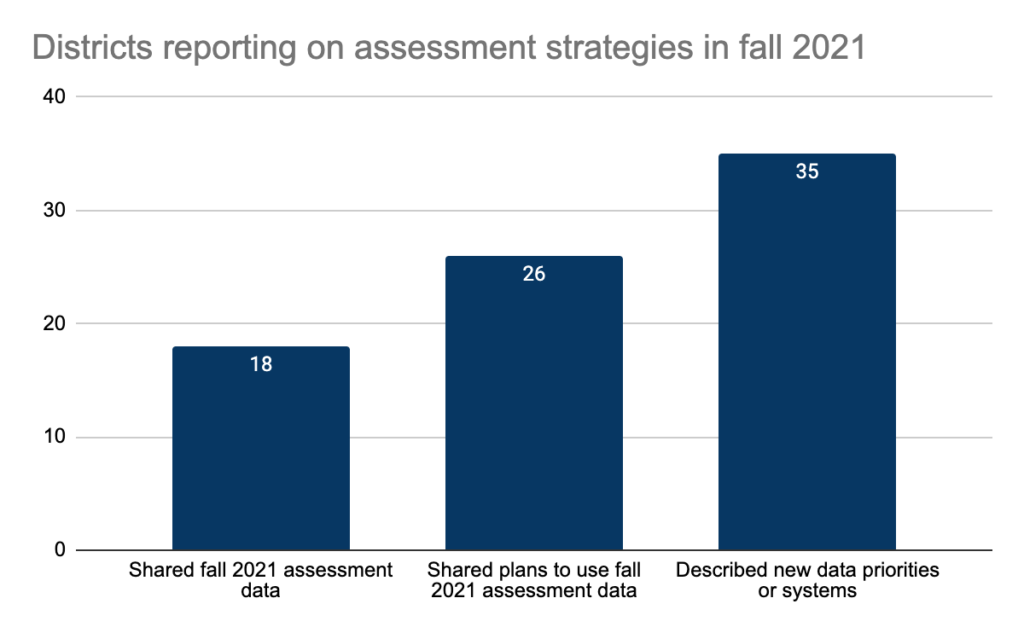

Only a fraction of these districts (18 of 70) shared the results publicly, however.

Roughly a quarter of districts (26) described how they would use data from these assessments, typically stating it would be analyzed to identify students in need of academic support. California’s Long Beach Unified school district, for example, employed i-Ready assessment data to identify students to receive tutoring support.

About one-third of districts (35) said they’re adopting new assessment systems or data priorities. Long Beach Unified also developed a new plan for a new assessment platform, progress monitoring tools and the use of comparative data to analyze student growth and acceleration.

In its American Rescue Plan application, the School District of Philadelphia outlined new plans to prioritize student well-being. Beginning in fall 2021, it implemented a social-emotional behavior screener to identify students in need of additional help. The application also stated plans to install a multi-tiered system of support in all schools this fall. While these examples highlight ways some districts are thinking about monitoring students’ academic and social-emotional statuses, the vast majority are not taking similar initiative.

It’s not too late to prioritize data collection efforts

While more districts have communicated their learning acceleration plans since 2020-21, it’s unclear how many have actually put them in motion and will continue them this year and next. A forthcoming study by CRPE, conducted as part of the American School District Panel, suggests that efforts have been slowed by staff and student absences.

It’s also unclear how many districts plan to monitor student progress or assess the effectiveness of these new strategies. Student progress data is not widely released to the public, as evidenced by the fact that less than 1 in 5 districts shared data on how students were faring in fall 2021.

In a separate analysis we conducted recently of spending plans for districts in New England, only 0.4% of relief funds were planned for data investments. Similarly, a FutureEd national analysis of spending plans found few districts planned to invest in student information systems. Overall, most districts don’t appear to be keeping data and progress monitoring top of mind. This isn’t to say that investments in learning acceleration are not well spent, but these efforts are less meaningful if school systems don’t have a plan to track how these strategies pay off in the long run.

Districts don’t have to be alone in organizing data collection efforts. States play a role in shaping how and what districts can do by requiring reports on important student metrics, such as assessment data, participation rates and chronic absenteeism levels. Connecticut has an accountability system that outlines 12 indicators to measure school and district success. The U.S. Education Department approved the state’s waiver to report on some of these metrics in 2021, when it was difficult to collect accurate data during school closures, but it will be important to continue gathering more information on students’ progress now that schools are operating in a new type of normal. More states must support data collection efforts as the country enters a new phase of recovery for students. Meanwhile, districts need to be honest about their capacity to carry out — and measure — the results of their planned learning recovery strategies.